In military history everything is explained by just two factors: mistakes and clash of egos. If historians of philosophy were less uptight I think they might do the same.

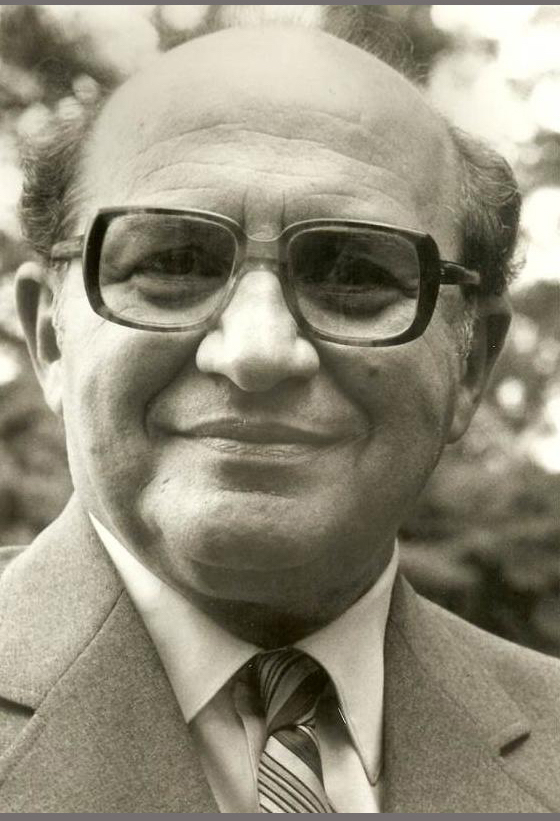

For graduate school I wanted to go to Pittsburgh because I had read an article by Adolf Grunbaum, their philosopher of science. He wrote as one in command, and not as the scribes.  As I began to see, reading more of his writings, he also conceived of philosophical debate as no-quarter, no holds barred, hand-to-hand combat. But this was entirely at odds with how he dealt personally with us students: with old-fashioned courtesy and respect, even sympathy, though not exactly moderating his uncompromising critique. When eventually I had submitted my first dissertation chapter draft I received it back with red ink comments on virtually every line. In my memory, as I told him later, I would see myself going to his office up some stairs with a print of a snarling wildcat. Both he and his secretary denied adamantly that there had ever been such a print, which means, I suppose, that the memory was a symptom of PTSD.

As I began to see, reading more of his writings, he also conceived of philosophical debate as no-quarter, no holds barred, hand-to-hand combat. But this was entirely at odds with how he dealt personally with us students: with old-fashioned courtesy and respect, even sympathy, though not exactly moderating his uncompromising critique. When eventually I had submitted my first dissertation chapter draft I received it back with red ink comments on virtually every line. In my memory, as I told him later, I would see myself going to his office up some stairs with a print of a snarling wildcat. Both he and his secretary denied adamantly that there had ever been such a print, which means, I suppose, that the memory was a symptom of PTSD.

In debate with other philosophers, most inevitably carried on in print rather than person, there was no sign of anything like his sympathy and care for us students. Which brings me to one of his opponents, a great ego whose presence was always on the edges of my consciousness: Sir Karl Popper.

I spent the year 1970-71 on a fellowship at Bedford College, in London’s Regent Park, with ample time to wander around its rose garden. The LSE was clearly London’s philosophy of science hub, and Popper’s department of logic and scientific method was famous — and notorious for its fabled autocratic, hierarchical style.

The first time I went there it was for a party with junior faculty and graduate students. I was quite out of my depths when the questions began: where did I stand on the Popper-Carnap debate? Which side did I take on deductivism versus inductivism? A bit too late I realized I should have read Popper and recent LSE papers … I could only waffle. But how could I do philosophy of science if I wasn’t up to date on these things? (The LSE students didn’t pull their punches, quite unlike the ones I had met at Bedford and University Colleges).

Going to their colloquia I soon came to understand what set them apart, and to realize how their conduct related to Popper’s intellectual ideals of audacious conjectures met by open and shut refutations. What it meant in practice was this:

a speaker would be confronted with a headlong charge purporting to refute everything he said. Then the charge would be at once, and graciously, abandoned at the first answer.

Popper would not always be there. If he was, and spoke, he would be accosted in precisely that way. After a while I conjectured audaciously (but silently) that what I was witnessing was training, the common cause of the participants’ shared manner of debate.

Which brings me to a Popper-Grunbaum confrontation where I happened to be present, sometime in the eighties. This was at LSE, in one of their annual symposia on the philosophy of Sir Karl Popper. When Grunbaum had turned to philosophy of psychoanalysis, in the seventies, he had begun an all-fronts attack on Popper’s view of the subject. Popper held that psychoanalysis is empirically irrefutable, and hence a pseudo-science. Grunbaum held the contrary: that it is empirically refutable, and was in fact empirically refuted.

As Grunbaum expressed this once again at the conference, Popper interrupted. Such Popper interruptions were dramatic. The moderator would notice that Popper had turned on his hearing aid, indicating that he wanted to speak, and would then at once stop all proceedings in mid-flow.

Popper challenged Grunbaum to present even one single example of an empirical refutation of Freud’s claims. Grunbaum gave one from Freud’s early work, in the 1890s. Popper replied “No, after 1900!” So Grunbaum gave another example from, if I remember correctly, 1918. Popper did not respond. I distinctly saw him fingering his hearing aid again.

But as soon as the official question period began W. W. Bartley III,  one of Popper’s followers, took the floor.

one of Popper’s followers, took the floor.

Going through Sir Karl’s writings, he said, I have found only three major passages about Freud, all short, besides a few incidental remarks including a mention of his sister. Counting the pages of Professor Grunbaum’s critiques I am already well beyond a hundred ... this is, I submit, an overreaction, in the clinical sense of the word.

The only time I saw Grunbaum livid, and speechless ….

*NOTES

The Popper Newsletter of March 1992 has a report on a one-day conference on the philosophy of Sir Karl Popper which begins in a revealing way with

“The main purpose of the Annual One-Day Conference on the Philosophy of Sir Karl Popper is to stimulate fruitful debate on Popper’s philosophy. Hence the challenging tone of the talks. Mere exposition is both boring and unproductive, and speakers are encouraged to be as critical as possible. Such a spirit of criticism is in line with Popper’s method of conjecture and refutation: bold guess followed by severe criticism.” (downloaded 5/17/2021 from http://www.tkpw.net/newsletter/v4n1-2/node32.html#SECTION000413000000000000000

Grunbaum began to criticize Popper with a two-part article (40 pages total) in 1977-78: “Is Psychoanalysis a Pseudo-Science? Karl Popper Versus Sigmund Freud”, That his style tended to be polemic must be admitted. After Grunbaum’s presidential address at the APA, in 1982, Ruth Barcan Marcus, then the Chair of the APA Board, received a letter asking that Grunbaum be reprimanded for expressing contempt for the work of other philosophers. The letter writer, though, was himself known for an aggressively adversarial style.

Following up on Professor Matthen’s point, I would like to offer two brief anecdotes. As a student in Vienna in the early 1980s, I remember a small conference in honor of the 80th birthday of Popper. The great man was there himself, listening to papers of mostly students. One of the papers defended a sort of cultural conceptual incommensurability, to which Popper only had one brief reply: “Young man, I really want to thank you for your very learned paper. However, I gave seminars where there were people from Africa, the Middle-East, Australia, and South America, and we all understood each other perfectly well. So I don’t know where this incommensurability is supposed to come from.” Around the same years, Gruenbaum had been invited to give a talk on his then new book on psychoanalysis. There was a big audience in the Festsaal of the old university building, including, apparently, an entire delegation of the Viennese Society for Psychoanalysis. After the talk ( I still vividly remember Gruenbaum’s disparaing but apt aside about Habermas’ “stone age physics”, which he allegedly used in defending the Geisteswissenschaften), a member of the Psychoanalytic Society rose from his seat to ask a question. It took him about 10 minutes of pontoficating before he came to his point, if there was one. Gruenbaum, smiling the entire time in the most friendly of manners, simply said after the chap was finished: ” You know, my dear fellow, the quality of a question fully determines the quality of the answer it deserves. Next.”

LikeLike

Lovely reminiscence of two great philosophers. Popper was right about one thing. In philosophy, all we have by way of “refutations” are dialectical challenges, and the old confrontational style was productive at least by making philosophical conjecture open to test in an otherwise irresponsible discipline. That said, there couldn’t really be characters much more obnoxious than Popper and Grunbaum!

LikeLike