When Calvino starts writing his memories of a battle he took part in thirty years before, he is at once in doubt. “Maybe all that’s left in my memory of the whole descent are these falls, which could equally be those of some other night or dawn.” After fourteen pages he writes “Everything I have written so far serves to show that I remember almost nothing of that morning now”.

Here I recognize the doubt that continually qualifies some of his own character’s stories, memories, assertions, their dominant sense of the fragility of truth. When he depicts someone not subject to any failing in this respect, it is Agilulf, the non-existent knight, an immaterial intelligence traipsing unhappily through our human mess and muddle.

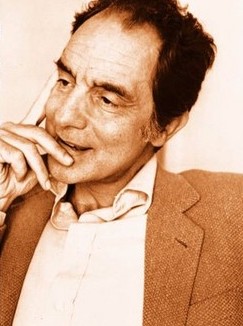

If now try to set down the few memories I have of Calvino, almost fifty years ago, it would show a quite misplaced arrogance if I just wrote them down linearly, blithely, unselfconsciously. Well, as if I were able to do so in the first place … In any case they lead me into a conflict: my memory’s voice is like the voice of another, of a bystander with unqualified authority, while my mind rebels, questions, attacks what it says.

At least this is true: I met Calvino at a conference in Florence in 1978, where I listened to him in simultaneous English translation. Happily he talked about one of my favorite stories, the story of Ulysses and the Sirens. He asked the unanswerable question “What were the Sirens singing?” and answered that perhaps it was the Odyssey itself that they sang.

Something special was arranged for the conference: a private tour through the museum corridor on the Ponte Vecchio.  As we strolled through I walked with Calvino’s wife, Chichita, who talked with much feeling about some of the religious themes in the paintings. Realizing how much Calvino was ‘on the other side’, I exclaimed “Vous n’êtes pas chrétienne?”. But yes, she answered, and why not? I think she recognized my smile, there in communist Florence, among the literati of the left ….

As we strolled through I walked with Calvino’s wife, Chichita, who talked with much feeling about some of the religious themes in the paintings. Realizing how much Calvino was ‘on the other side’, I exclaimed “Vous n’êtes pas chrétienne?”. But yes, she answered, and why not? I think she recognized my smile, there in communist Florence, among the literati of the left ….

But how could this possibly be right? She was born Jewish, from Argentine … Those paintings were on Christian themes though … Still … Perhaps I said “croyante” rather than “chrétienne”? Or perhaps she answered playfully, and I missed what she meant?

My memory shouts me down: what I remember is what it was! A memory is not a theoretical thing to speculate about, a memory is vivid, direct, it speaks with the voice of an angel,

But do angels speak the truth?

Does anyone, however hard they try? In The Castle of Crossed Destinies the travelers are struck dumb and tell their stories by laying out tarot cards. Their stories, from their failing and fictionalizing memory, go then through the prism of the others’ failing, fictionalizing reading of the cards. So the story we end with is at three removes from truth. What Plato said of art holds always.

In a break, of one sort or another, I was next to their daughter Giovanna, who was I think about thirteen at the time. Whatever she was telling me, what I remember is that I was confused about whether “ennui” meant annoyance or just boredom … and that she was laughing. Probably about my miserable French, but not unkindly.

None of this is out of the ordinary, but it is extraordinary for me simply because I was, and am, so in awe of Calvino, of the way he writes, like a philosopher’s fantasy of a novelist.

None of this is out of the ordinary, but it is extraordinary for me simply because I was, and am, so in awe of Calvino, of the way he writes, like a philosopher’s fantasy of a novelist.

In the sixties, when I was at Yale, I had become friends with an editor of the Yale Press, Jane. She gave me a mission when I went to Los Angeles, to convince Richard Montague to let her publish a collection of his papers. I remember the meeting (Montague came to my friend Sidney’s party in a gold Rolls-Royce), but had the impression that nothing came of it. Something must have, for a few years later, after he died, Yale published a collection of his papers, edited by Rich Thomason.

I mention this seemingly totally irrelevant fact, to explain how it happened that I met Calvino again. Jane had moved to a publisher in New York, I had left Yale, but — probably at some conference — when I told her about Calvino’s speech in Florence she said: go see him, tell him I’d like to publish not his novels but talks, lectures, like the one you are telling me about. So that year when I was in Italy, Calvino was kind, he invited me to their apartment in Rome, to talk about it. Somehow, by whatever design, the apartment’s focal point was a cluster of photos of Giovanna. Chichita wanted to talk about her — Giovanna was in Paris, rebellious, caught up in student life …. words that inevitably bear images of the Left Bank, street protest, Colette, Henry Miller …. Who could say?

Calvino was courteously disinterested in more publishing possibilities.