A fateful decision could be minor in either of two ways. It could be the sort of decision that elsewhere and elsewhen has led to tragedy, but in this particular case the actor gets off scot=free, Or it could be minor in that the decision was in itself of no great consequence, though the outcome could have been tragic.

This is going to be about two fateful decisions that were minor in both ways. Poor marketing strategy! It means that in the end they were negligible, the decision itself was not dramatic, and no one got hurt– so, who cares? Look at all those people watching in those climbing movies, Dawn Wall and Free Solo. Why are their hearts in their mouths, and why did so many of them come? Because they are watching whole sequences of major fateful decisions and imaging the great drama of violent death.

Every year the Alpine Club publishes Accidents in North American Climbing. Just the facts, ma’am, straightforward reports from rangers and other climbers, data to reduce death and dismemberment to statistics. Free to the members, but it can be bought by anyone, pdf or print, very cheaply. The Club is missing a bet here, and a great source of funds! With all that prurient interest ready to be tapped …. Some gleeful writing about the silly mistakes, some bloody pictures too, and they’d make the New York Times best-seller list every time.

Every year the Alpine Club publishes Accidents in North American Climbing. Just the facts, ma’am, straightforward reports from rangers and other climbers, data to reduce death and dismemberment to statistics. Free to the members, but it can be bought by anyone, pdf or print, very cheaply. The Club is missing a bet here, and a great source of funds! With all that prurient interest ready to be tapped …. Some gleeful writing about the silly mistakes, some bloody pictures too, and they’d make the New York Times best-seller list every time.

I cannot offer anything like such excitement. Worse: I will not be able to avoid all of the tiresome details that are so fascinating to climbers and so boring for everyone else. It was sometime in the 1990s that I went climbing with Keith (or was his name Kevin?) on the Stately Pleasure Dome in Tuolumne.

On the left side of this picture you see an obvious feature pointing up: its top is Hermaphodite Flake, and the blank part after that has several good bolted routes. One leads up and to the right: Eunuch (5.7R), the line I have drawn straight. The R stands for “Runout”, which means that some protection is scarily far apart. So Keith and I climbed up to Hermaphrodite Flake, crawled through underneath it, and turned to Eunuch.

On the left side of this picture you see an obvious feature pointing up: its top is Hermaphodite Flake, and the blank part after that has several good bolted routes. One leads up and to the right: Eunuch (5.7R), the line I have drawn straight. The R stands for “Runout”, which means that some protection is scarily far apart. So Keith and I climbed up to Hermaphrodite Flake, crawled through underneath it, and turned to Eunuch.

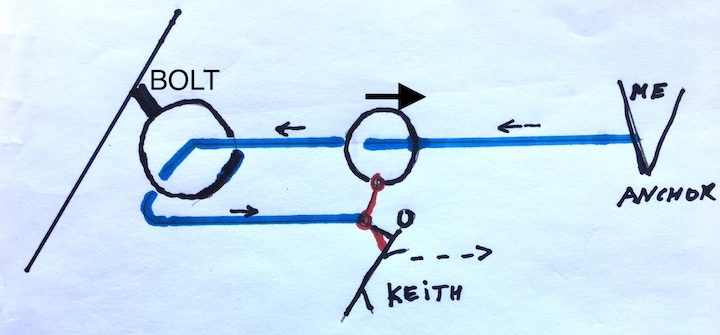

The exposed pitch I led had the run-out section, a long traverse with nothing but featureless slab below. I anchored myself at the end, and told Keith “You are on belay”. Now Keith had been to a mountaineering course, which emphasized a very professional attitude toward eliminating danger. When he got to the last bolt before me, at the start of the traverse, he stopped. If he fell on the traverse, he pointed out, he would swing and could hit the facing rock. So he set out to eliminate this danger in a clever way. He threaded the rope through the bolt where he was standing, and set off toward me, but with himself clipped to that still part of the rope. No way to fall at all!

When he reached me and attached himself to my anchor, everthing should have been easy. He undid the rope from his harness, and asked me to start pulling it in on my end. Beautiful …. except that when his end of the rope reached that last bolt, it turned out that he had left a knot in it, the figure 8 knot used to secure his harness. And the knot would not go through the bolt. We looked at each other. “One of us has to go there, back across the traverse”, I said, looking pointedly, and not charitably, at him who had left in the knot. “And then do the traverse this way back.”

This was a point of fateful decision for Keith. He got quite angry (at fate, presumably). But he could see more clearly than me. He had a knife in his pocket, and slashed off the nearly 30 feet of rope behind us. A Gordian moment! We finished the route with a 50 meter rope, and it worked.

I admit –a bit ashamed — being Dutch I was happy it had been his rope.

| But my turn came, sure enough, to be in a position quite like Keith’s. That was on a great adventure with Ric Otte, Alvin Plantinga, and four other friends: climbing Lost Arrow Spire in Yosemite. We began by hiking up along the waterfalls to the Valley Rim. We would then rappel down to get to the bottom of the spire – next climb the spire — and next, get back to the Rim by Tyrolean traverse. |

In my team Derek led, Ric free climbed following him, and I, the least experienced, jumared up on a second rope. They had given me a jumaring lesson the day before, not omitting safety tips and advice about how not to hang upside down. There would be much to tell, but let me get at once to the Tyrolean traverse.

Mechanically it is a lot like the diagram for Keith’s set-up. The difference is that Keith could walk, while here you were hanging on the rope, your feet in two etriers (a sort of personal rope ladder), and had to use your jumars to pull yourself forward. And a thousand feet or so below you see the roof of the Ahwahnee hotel …

Mechanically it is a lot like the diagram for Keith’s set-up. The difference is that Keith could walk, while here you were hanging on the rope, your feet in two etriers (a sort of personal rope ladder), and had to use your jumars to pull yourself forward. And a thousand feet or so below you see the roof of the Ahwahnee hotel …

| Midway one of my jumars got stuck. I could not move forward or backward. Did I face one fateful decision or a whole series of them? Perhaps a truly experienced climber would have had the various slings, etriers, carabiners, and jumars so arranged as to fix it quickly and elegantly — well, … I began to tie slings and untie them, constantly telling myself to check that I undid nothing unless something else was protecting me I saw one of my etriers fluttering down, like a falling leaf … OK, I got the jumar loose, now without an etrier. And then I got myself forward on one leg and some improvised ways of using the wayward jumar. |

Jumars don’t get stuck, let alone difficult to do and undo, without some serious pro handling mistakes. Gods of the mountains, forgive me!

But well, just minor after all … never a mention in the Alpine Club news ….