Etruscan Places

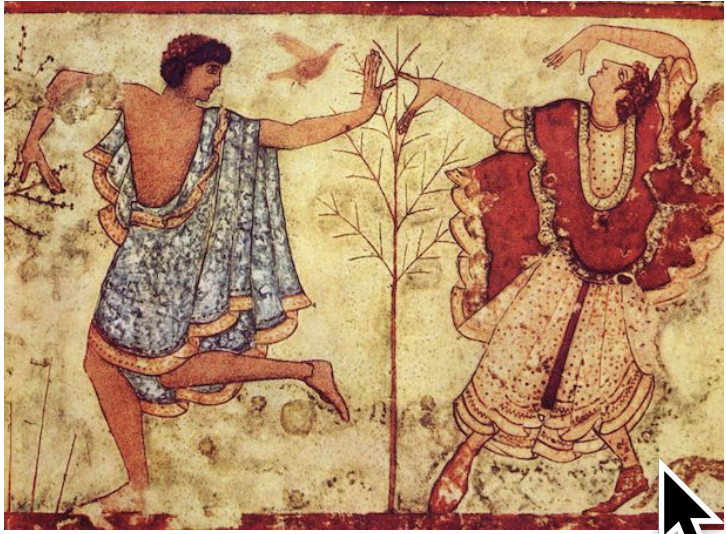

The Etruscans are a mystery, although the Romans’ drastic ethnic cleansing still left clues. There are tombs, frescoes, smiling sculptures, vivid with a sense of life lived differently from their conquerors. For us, besides the tombs, there is mainly the film, Jules et Jim, with Jeanne Moreau’s Etruscan smile.

In Margarite Duras’ novel The Little Horses of Tarquinia the characters do not get so far as to actually see those horses. They are spending a week’s holiday in a little Italian village, between mountains and the sea, with nothing to do, enervated by the heat, talking in a futile, desultory way about how they could go elsewhere.

Near the end of the week Jacques and Sara’s difficult relationship turns into a plan to go see the little horses of Tarquinia. The novel ends before they go. But if there is redemption gained in this story, it is through the project itself, through committing to this project to go see the little horses. Duras allows an insight to appear in one of the many voices around them: there are no holidays from love, you have to live it fully, boredom and all, you can’t take anything away from it.

Near the end of the week Jacques and Sara’s difficult relationship turns into a plan to go see the little horses of Tarquinia. The novel ends before they go. But if there is redemption gained in this story, it is through the project itself, through committing to this project to go see the little horses. Duras allows an insight to appear in one of the many voices around them: there are no holidays from love, you have to live it fully, boredom and all, you can’t take anything away from it.

A little ironic? They have spent the week fruitlessly attempting to enjoy a vacation from their ordinary life, from the others, from themselves … Is that the sense of impossibility of a holiday, that is meant? Or can we trust the sense of relief, of hope?

I began to wonder what Duras had presupposed, perhaps required, of her model reader. Would some knowledge of the Etruscans make the reference to Tarquinia, in this story, entirely transparent?

Some time in the mid-seventies I went with two companions to spend the summer in Tuscany, to discover Etruscan places and remains, to see the Etruscan horses of Tarquinia, and much else. Equipped with two tents and an old car, we would seek out the scattered tombs or sanctuaries in villages and farm fields, especially those still preserved but unsung.  We had a Michelin guide, which helped with the itinerary but gave little guidance to find non-Roman remains. And I remember a book, or perhaps several books, now quite lost, that gave directions not only to the famous necropoles but to Etruscan places in the countryside.

We had a Michelin guide, which helped with the itinerary but gave little guidance to find non-Roman remains. And I remember a book, or perhaps several books, now quite lost, that gave directions not only to the famous necropoles but to Etruscan places in the countryside.

I remember odd phrases, like “Ask for the custodian in the village — he is normally to be found on the bowling green”. And then the custodian would, sometimes a bit grumpily, fetch the key, unlock the door in what had looked like a small hill, let us in to the tomb. These small rural sites were not so spectacular but gave us the pleasant sense that, as itinerant but respectable vagrants, we were seeing much more than the usual visitors.

I remember odd phrases, like “Ask for the custodian in the village — he is normally to be found on the bowling green”. And then the custodian would, sometimes a bit grumpily, fetch the key, unlock the door in what had looked like a small hill, let us in to the tomb. These small rural sites were not so spectacular but gave us the pleasant sense that, as itinerant but respectable vagrants, we were seeing much more than the usual visitors.

Tarquinia is rather high up, overlooking the sea, and the great necropolis is not far away. What was left in the tombs was not at all just about death, rather, I would say, it was about death so as to show much about life.

In the Cerveteri tomb of a woman of high rank, all her gold ornaments and silver vessels accompany her, as well as  her four-wheeled carriage and — surely this points to the aspects of life she cherished most? — her bronze bed.

her four-wheeled carriage and — surely this points to the aspects of life she cherished most? — her bronze bed.

So many years ago. We would put up our tents in this campsite or that, or sometimes in a farmer’s field. Near the southern point in our slow meander we suddenly found ourselves overlooking Lago Bolsena, the lake of the Etruscans. There was a story of the Etruscans moving, after destruction of their town where Orvieto is now, to the Volsini mountains, overlooking the lake. We moved slowly, over a number of days, around the lake, and I have vague images of a tomb called the Red Tomb, but can find no reference to it now.

If Duras’ characters did go on to Tarquinia, what did they feel, and what did it do to them, seeing those paintings of abundant life, love, feasts and dances, horses and lions?

My friend Arnold Burms, speaking about literature much later, said that the real mystery about stories is that we wonder how it came out, even though we know that there is nothing beyond what the author wrote. We do not wonder about all the ways the author could have continued: no, we wonder what happened next, what did happen in the end. Novelists can try to stop us from continuing with that question. They can end with “Reader, I married him!’ or with a ride off into the sunset, or a death, but the question lingers. And sometimes it is just what makes us never forget the story. Now, with my ever fainter memories of Etruscan places, I realize that it is a question not just posed by novels, but by the stories in our memory. And sometimes the answer can only remain forever that the story’s meaning is what it will have been, when all else is told.

————– ————

Il n’y a pas de vacances à l’amour, … ça n’existe pas. L’amour, il faut le vivre complètement avec son ennui et tout, il n’y a pas de vacances possibles à ça.

– Et c’est ça l’amour. S’y soustraire, on ne peut pas. Comme à la vie, avec sa beauté, sa merde et son ennui. (Margarite Duras, Les petits chevaux de Tarquinia)