…. and its failures

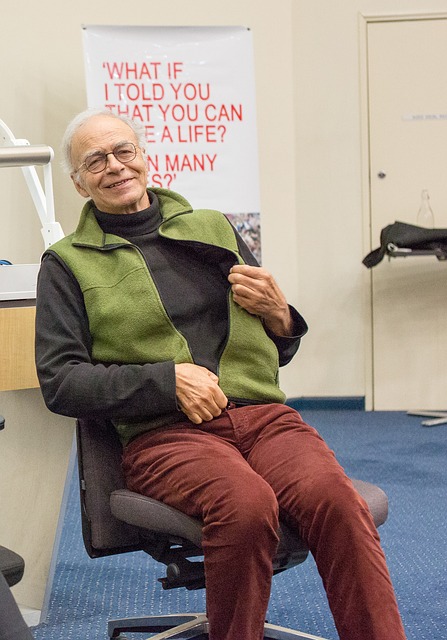

Peter Singer is much to be admired, for all the good he has done for animal rights and welfare. But he encountered much hostility, not for his naïve utilitarianism (let’s draw a veil, shall we?) but for his reasons for not eating animals. Some of the criticism in the German-speaking countries tended toward violence, even near riots in Austria. This was before the flowering of social media, but the internet was already spreading abuse of all sorts. Soon after Singer came to Princeton I came upon something on the web, an article ostensibly praising bestiality, advocating sex with animals, purporting to be by Peter Singer. and posted under his name.

Peter Singer is much to be admired, for all the good he has done for animal rights and welfare. But he encountered much hostility, not for his naïve utilitarianism (let’s draw a veil, shall we?) but for his reasons for not eating animals. Some of the criticism in the German-speaking countries tended toward violence, even near riots in Austria. This was before the flowering of social media, but the internet was already spreading abuse of all sorts. Soon after Singer came to Princeton I came upon something on the web, an article ostensibly praising bestiality, advocating sex with animals, purporting to be by Peter Singer. and posted under his name.

Later that day, meeting my colleague Beatrice Longuenesse, a good friend of Singer’s, I expressed my dismay. “Criticism is all very well”, I said, “but to actually go so far as to publish a parody of his views, under his own name, that is outrageous”. She looked at me, startled, and then looked suddenly quite angry — that was not a parody! it was his, what was I thinking of, what did I mean? What was I trying to say?

I was startled in turn … embarrassed at my faux pas. Parody, when it succeeds, is admirable as a literary tour de force, but perhaps it goes wrong all too often. (As it did, on this occasion, in the opposite way so to speak, by my taking something as parody that wasn’t.)

Famous examples of parody, their blend of irony and innocence, are a delight. When Thomas Mann had become quite famous in his own right he could take on the most famous of German writers, with a parody of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s autobiography. That this autobiography, Truth and Poetry: from My Own Life,  was fertile ground for growing parody seems incontestable. As Goethe looks back so glowingly on his childhood, for example:

was fertile ground for growing parody seems incontestable. As Goethe looks back so glowingly on his childhood, for example:

On the night before Whit Sunday, not long since, I dreamed that I stood before a mirror, engaged with the new summer clothes which my dear parents had given me for the holiday. The dress consisted, as you know, of shoes of polished leather, with large silver buckles, fine cotton stockings, black nether garments of serge, and a coat of green baracan with gold buttons. The waistcoat of gold cloth was cut out of my father’s bridal waistcoat. My hair had been frizzled and powdered, and my curls stuck out from my head like little wings … (beginning of Second Book)

In fine imitation Mann wrote Felix Krull, Confessions of a Confidence Man: the Early Years,  narrated in an equally glowing tone, always a bit overly so, by an amusing crook. Amusing in its own right, it is all the more so when reading Goethe alongside. Of course Mann raises the stakes: such passages as “Since that impassioned girl had cursed and sanctified my lips (for every consecration involves both)”

narrated in an equally glowing tone, always a bit overly so, by an amusing crook. Amusing in its own right, it is all the more so when reading Goethe alongside. Of course Mann raises the stakes: such passages as “Since that impassioned girl had cursed and sanctified my lips (for every consecration involves both)”  have as their counterparts passages considerably less inhibited. And the self-admiration is made just a touch more salient in Krull:

have as their counterparts passages considerably less inhibited. And the self-admiration is made just a touch more salient in Krull:

The connoisseur of humanity will be interested in the way my penchant for two-fold enthusiasms, for being enchanted by double-but-dissimilar, was called into play by this mother-and-daughter …. I, at all events, find it very interesting.

Admiring this style, I also tried my hand at it, but naturally in my proper milieu, a philosophical debate. Deciding to stick a little thorn in the sides of scientific realists, I wrote a paper ‘Theoretical Entities: The Five Ways’.  Thomas Aquinas’ Five Ways were his five proofs of the existence of God, still taken seriously in the most traditional Thomist circles. In imitation thereof, pretending to be converted now to scientific realism, I wrote five proofs of the existence of unobservable entities, like electrons, quarks, or fields.

Thomas Aquinas’ Five Ways were his five proofs of the existence of God, still taken seriously in the most traditional Thomist circles. In imitation thereof, pretending to be converted now to scientific realism, I wrote five proofs of the existence of unobservable entities, like electrons, quarks, or fields.

The initial reactions surprised me. Ronnie de Sousa was in England just then, and wrote me a detailed letter to show that my proofs were not valid. Just a week later Ronnie send me an embarrassed postcard, with a drawing of himself with mud on his face. A philosopher whose name I forget (but would not name here if I remembered) wrote to say that he was compiling an anthology of articles about Aquinas’s Five Ways, could he include my paper? Then Clark Glymour laughingly told me that David Lewis had come to his office, my article in hand, asking worriedly whether I was serious?

So it seemed that my attempt to parody had misfired. Most likely it had simply not been transparent enough. When I included it as the last chapter in the book I was then writing, I gave it the new title, “Gentle Polemics”. Then I added a footnote to make its intent crystal clear, “My reason for writing [this] was the remark of an eighteenth-century wit that everyone believed in the existence of God till the Boyle lecturers proved it”. In retrospect I can only say that my effort found no welcome. Not a single review or critical article ever mentioned my so lovingly crafted literary exercise.

Parody is alive today, everywhere, in popular culture — witness The Daily Show, Saturday Night Live, or Yankovic’s “Like a Surgeon” spoof of Madonna. But is there a welcome anywhere in academia, now so very professionalized and compartmentalized, if parody is practiced and not just commented on? Sarcasm, irony, and even gentle parody can cut just a little to close to the bone. It may be best, finally, to avoid parody when writing a philosophical paper, on pain of the sort of response we’d hear in the old West’s saloons,

“Smile when you say that, stranger!”

with hand straying toward the holstered six-gun.