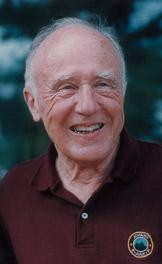

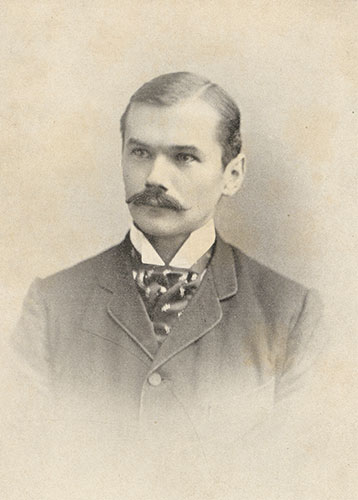

Recently I found on my shelves a dissertation on how relativity was received in the Netherlands, and began (at long last!) to read it. One name struck me immediately: Frederik van Eeden. For by coincidence I had just been reading him about lucid dreams, of which he had recorded some 500 in a diary.

What is famous in the Netherlands may be quite unknown elsewhere. That is probably so for van Eeden, and for his children’s book De kleine Johannes (‘The Little Johannes’), a classic to be read equally well by adults. That I found also, for a long time unread, on my book shelves.

What is famous in the Netherlands may be quite unknown elsewhere. That is probably so for van Eeden, and for his children’s book De kleine Johannes (‘The Little Johannes’), a classic to be read equally well by adults. That I found also, for a long time unread, on my book shelves.

What any of this has to do with relativity is that van Eeden was living through a time of radical and revolutionary changes in his surrounding intellectual environment, both in physics and elsewhere, and was an active voice in those changes. But let me go back to the beginning.

When still a young man van Eeden gained immediate fame with this children’s story. If it were published today in America, school boards would be falling all over themselves to ban it from the libraries. It begins as a fairy-tale idyll:

“It was warm and the pond was entirely still. The sun, red and tired of her day’s work seemed to rest for a moment on the dunes’ edge before she went under …”

Little Johannes, dozing dreamily in a little boat on the pond, is beckoned by a blueish winged elf, and goes along. He is taken to talk with all the small animals in the fields, and hears the cruel destructive impact by humans, obliviously or cruelly roughshod, how they are a plague and a scourge upon the earth. As he grows up, taken along by other fairy tale characters, he comes to see the systematic cruelty of human society exercised upon the humans themselves as well. Johannes wants not to be human, does not want to join the human world, but being born human he has no choice. To live, he is told again and again, he must stunt his sensitivity, if it is to be possible to live as a human at all. He watches with dismay his own faltering steps toward and away from that world so far and so different, so wrong and so miserable, from how his journey began.

Only at the end of the book, for one who has witnessed all the misery and depravity in the world, redemption seems possible.

Meanwhile, in the 1890s, Lady Victoria Welby, maid of honor to Queen Victoria, invited writers, philosophers, and scientists to her salon. A few years after De kleine Johannes she met van Eeden at the Congress of Experimental Psychology, and they were an immediate match. This meeting began a long conversation and correspondence on her theme topic, language, meaning, and clarity. Their cooperation founded Significs, a form of philosophy of language, which began with her 1896 essay in Mind and van Eeden’s 1897 book written in Dutch.

Meanwhile, in the 1890s, Lady Victoria Welby, maid of honor to Queen Victoria, invited writers, philosophers, and scientists to her salon. A few years after De kleine Johannes she met van Eeden at the Congress of Experimental Psychology, and they were an immediate match. This meeting began a long conversation and correspondence on her theme topic, language, meaning, and clarity. Their cooperation founded Significs, a form of philosophy of language, which began with her 1896 essay in Mind and van Eeden’s 1897 book written in Dutch.

Philosophical discussion circles, such as those of Lady Victoria Welby’s salon,were strewn randomly all across Europe in those days. They are now mainly forgotten, except those that eventually evolved into ones we must count as our ancestors: the Vienna Circle, the Berlin Circle, and yes, believe me, the Significs Circle, which ran the still flourishing journal Synthese for its first half-century.

Van Eeden brought Lady Welby’s themes to the Netherlands, to discussions with the mathematicians Mannoury, who introduced mathematical logic there, and his (later so famous) student L. E. J. Brouwer. These meetings, which soon involved others, started very early in the century, and remained closely connected to Brouwer’s Intuitionism.

It was, of course, in just those early years of the century when Einstein’s relativity theory made its sudden, violent impact on our thinking. (Hard to realize now, just how hard it hit then, when today everyone accepts it as understood and not in any way disquieting … ) There are many stories to be told about this impact, both within physics and in the wider intellectual world. William Magie, president of the American Physical Society wrote “the abandonment of the hypothesis of an ether … is a great and serious retrograde step ….”. It was loss of an explanation, and how can we be at peace when things remain unexplained?

For van Eeden the intellectual impact came in conjunction with a greatly felt personal loss, the death of his son Paul. Writing about this he reflected:

“What is the source of gloom? … It is doubt, uncertainty. The frightening insight in the limited reach of all our knowledge. We sense ourselves in the midst of a cosmos that is on every side too large, with means for understanding that fall short on every side. The more we think, the more we realize the vanity of all our knowing. The closest, most general concepts appear false, illusions, mere aids to get along, crutches for our lame understanding. Space is an illusion, unity of time is an illusion, the simplest truths of mathematics can be altered, it is possible for a non-Euclidean geometry to exist beside the Euclidean. The scientifically-true is intuitively-impossible, and most trusted supports for our spirit turn upon rigorous analysis into misty illusions.”

His was not a lone voice. While Einstein and Lorentz, the great protagonists, were good friends and respected each other’s view, and the younger Dutch physicists like Fokker patiently explained the theory’s implications and lack thereof, other writers ranged themselves in metaphysically and theologically marked heated controversies.

Van Eeden expressed the felt sense of loss, without resistance to the great changes he was living through, yet, like Johannes, without loss of hope.

REFERENCES

(The two quotes are from van Eeden’s writings, my translations.)

Klomp, Henk A. (1997) De Relativiteitstheorie in Nederland. Epsilon.

Van Eeden, Frederik (1897) Redekunstige grondslag van verstandshouding. Amsterdam: Versluys; reprinted 1975 Utrecht: Het Spectrum, with introduction by Bastiaan Willink. https://www.dbnl.org/titels/titel.php?id=eede003stud03

Van Eeden, Frederik (1914) Paul’s ontwaken. Amsterdam: Versluys. https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/eede003paul02_01/colofon.php

Welby, Lady Victoria (1896) “Sense, meaning, and interpretation”. Mind N. S. 5: 24-37, 186-202.

Rather, the problem as posed in Simone Weil’s meditation on the Iliad, Le Poème de la Force. As the Iliad’s heroes, Greeks and Trojans both, act on their anger and lust of violence, the idea of their honor and revenge, are they paradigmatically free actors? Or, being gripped by emotion are they no more free than leaves blown off a tree, fluttering to the ground?

Rather, the problem as posed in Simone Weil’s meditation on the Iliad, Le Poème de la Force. As the Iliad’s heroes, Greeks and Trojans both, act on their anger and lust of violence, the idea of their honor and revenge, are they paradigmatically free actors? Or, being gripped by emotion are they no more free than leaves blown off a tree, fluttering to the ground?  What is Piccolino? He is a slave, his mother sold him. He is an object, a piece of property bought and sold, used. He is given as a plaything to the child Angelica, and as an object of scientific study to Bernardo, and he feels it deeply, “inside I am raging with fury”. He struggles to define himself in face of the facts of his situation,

What is Piccolino? He is a slave, his mother sold him. He is an object, a piece of property bought and sold, used. He is given as a plaything to the child Angelica, and as an object of scientific study to Bernardo, and he feels it deeply, “inside I am raging with fury”. He struggles to define himself in face of the facts of his situation,  Simone Weil’s, L’Iliade ou le poème de la force, written early in the war, begins “The true hero, the true subject, the center of the Iliad, is force. Force that is managed by man, force that enslaves man, force before which man’s flesh flinches. A human soul appears always modified by its relations with force, as swept away, blinded, by the very force it believed itself able to handle, bent by the force that constrains it.” (my tr.) Les Cahiers du Sud 1940/41.

Simone Weil’s, L’Iliade ou le poème de la force, written early in the war, begins “The true hero, the true subject, the center of the Iliad, is force. Force that is managed by man, force that enslaves man, force before which man’s flesh flinches. A human soul appears always modified by its relations with force, as swept away, blinded, by the very force it believed itself able to handle, bent by the force that constrains it.” (my tr.) Les Cahiers du Sud 1940/41.

At the Vanguard she started slowly, a sort of jazz lullaby, but that was a truly deceptive beginning. By the end it felt like we had come through a storm, she had turned wild, at one point climbing on the piano stool, I swear I saw her kicking the keys with her foot.

At the Vanguard she started slowly, a sort of jazz lullaby, but that was a truly deceptive beginning. By the end it felt like we had come through a storm, she had turned wild, at one point climbing on the piano stool, I swear I saw her kicking the keys with her foot.

The universe creating itself through observation

The universe creating itself through observation