Etruscan Places

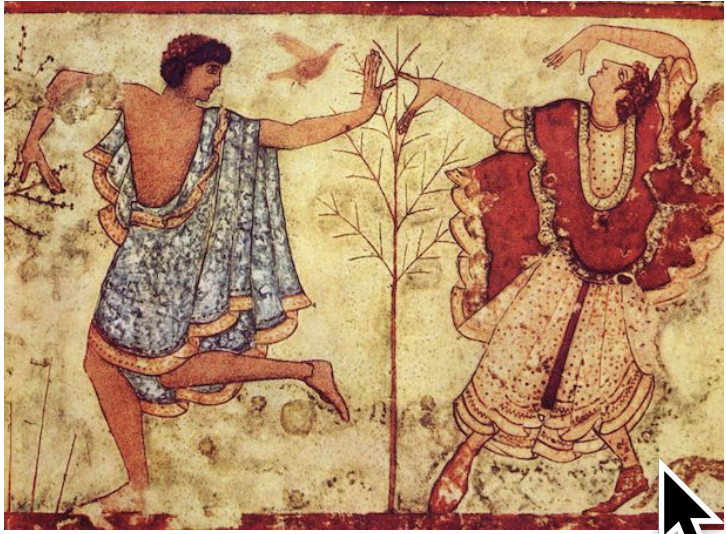

The Etruscans are a mystery, although the Romans’ drastic ethnic cleansing still left clues. There are tombs, frescoes, smiling sculptures, vivid with a sense of life lived differently from their conquerors. For us, besides the tombs, there is mainly the film, Jules et Jim, with Jeanne Moreau’s Etruscan smile.

In Margarite Duras’ novel The Little Horses of Tarquinia the characters do not get so far as to actually see those horses. They are spending a week’s holiday in a little Italian village, between mountains and the sea, with nothing to do, enervated by the heat, talking in a futile, desultory way about how they could go elsewhere.

Near the end of the week Jacques and Sara’s difficult relationship turns into a plan to go see the little horses of Tarquinia. The novel ends before they go. But if there is redemption gained in this story, it is through the project itself, through committing to this project to go see the little horses. Duras allows an insight to appear in one of the many voices around them: there are no holidays from love, you have to live it fully, boredom and all, you can’t take anything away from it.

Near the end of the week Jacques and Sara’s difficult relationship turns into a plan to go see the little horses of Tarquinia. The novel ends before they go. But if there is redemption gained in this story, it is through the project itself, through committing to this project to go see the little horses. Duras allows an insight to appear in one of the many voices around them: there are no holidays from love, you have to live it fully, boredom and all, you can’t take anything away from it.

A little ironic? They have spent the week fruitlessly attempting to enjoy a vacation from their ordinary life, from the others, from themselves … Is that the sense of impossibility of a holiday, that is meant? Or can we trust the sense of relief, of hope?

I began to wonder what Duras had presupposed, perhaps required, of her model reader. Would some knowledge of the Etruscans make the reference to Tarquinia, in this story, entirely transparent?

Some time in the mid-seventies I went with two companions to spend the summer in Tuscany, to discover Etruscan places and remains, to see the Etruscan horses of Tarquinia, and much else. Equipped with two tents and an old car, we would seek out the scattered tombs or sanctuaries in villages and farm fields, especially those still preserved but unsung.  We had a Michelin guide, which helped with the itinerary but gave little guidance to find non-Roman remains. And I remember a book, or perhaps several books, now quite lost, that gave directions not only to the famous necropoles but to Etruscan places in the countryside.

We had a Michelin guide, which helped with the itinerary but gave little guidance to find non-Roman remains. And I remember a book, or perhaps several books, now quite lost, that gave directions not only to the famous necropoles but to Etruscan places in the countryside.

I remember odd phrases, like “Ask for the custodian in the village — he is normally to be found on the bowling green”. And then the custodian would, sometimes a bit grumpily, fetch the key, unlock the door in what had looked like a small hill, let us in to the tomb. These small rural sites were not so spectacular but gave us the pleasant sense that, as itinerant but respectable vagrants, we were seeing much more than the usual visitors.

I remember odd phrases, like “Ask for the custodian in the village — he is normally to be found on the bowling green”. And then the custodian would, sometimes a bit grumpily, fetch the key, unlock the door in what had looked like a small hill, let us in to the tomb. These small rural sites were not so spectacular but gave us the pleasant sense that, as itinerant but respectable vagrants, we were seeing much more than the usual visitors.

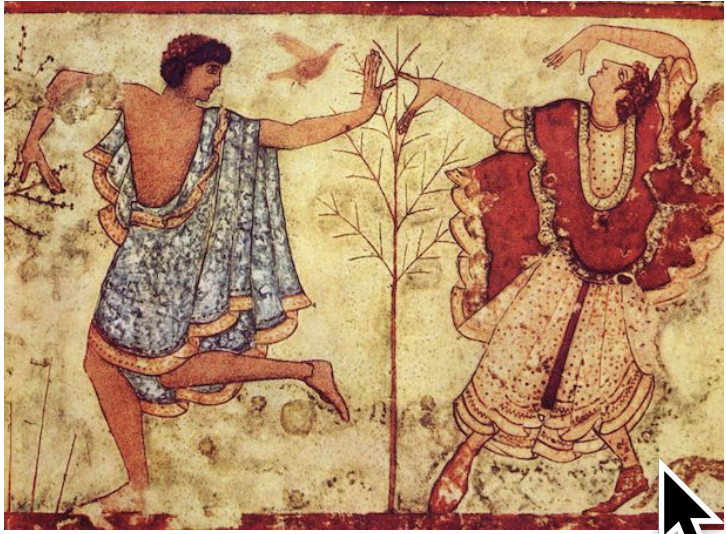

Tarquinia is rather high up, overlooking the sea, and the great necropolis is not far away. What was left in the tombs was not at all just about death, rather, I would say, it was about death so as to show much about life.

In the Cerveteri tomb of a woman of high rank, all her gold ornaments and silver vessels accompany her, as well as  her four-wheeled carriage and — surely this points to the aspects of life she cherished most? — her bronze bed.

her four-wheeled carriage and — surely this points to the aspects of life she cherished most? — her bronze bed.

So many years ago. We would put up our tents in this campsite or that, or sometimes in a farmer’s field. Near the southern point in our slow meander we suddenly found ourselves overlooking Lago Bolsena, the lake of the Etruscans. There was a story of the Etruscans moving, after destruction of their town where Orvieto is now, to the Volsini mountains, overlooking the lake. We moved slowly, over a number of days, around the lake, and I have vague images of a tomb called the Red Tomb, but can find no reference to it now.

If Duras’ characters did go on to Tarquinia, what did they feel, and what did it do to them, seeing those paintings of abundant life, love, feasts and dances, horses and lions?

My friend Arnold Burms, speaking about literature much later, said that the real mystery about stories is that we wonder how it came out, even though we know that there is nothing beyond what the author wrote. We do not wonder about all the ways the author could have continued: no, we wonder what happened next, what did happen in the end. Novelists can try to stop us from continuing with that question. They can end with “Reader, I married him!’ or with a ride off into the sunset, or a death, but the question lingers. And sometimes it is just what makes us never forget the story. Now, with my ever fainter memories of Etruscan places, I realize that it is a question not just posed by novels, but by the stories in our memory. And sometimes the answer can only remain forever that the story’s meaning is what it will have been, when all else is told.

————– ————

Il n’y a pas de vacances à l’amour, … ça n’existe pas. L’amour, il faut le vivre complètement avec son ennui et tout, il n’y a pas de vacances possibles à ça.

– Et c’est ça l’amour. S’y soustraire, on ne peut pas. Comme à la vie, avec sa beauté, sa merde et son ennui. (Margarite Duras, Les petits chevaux de Tarquinia)

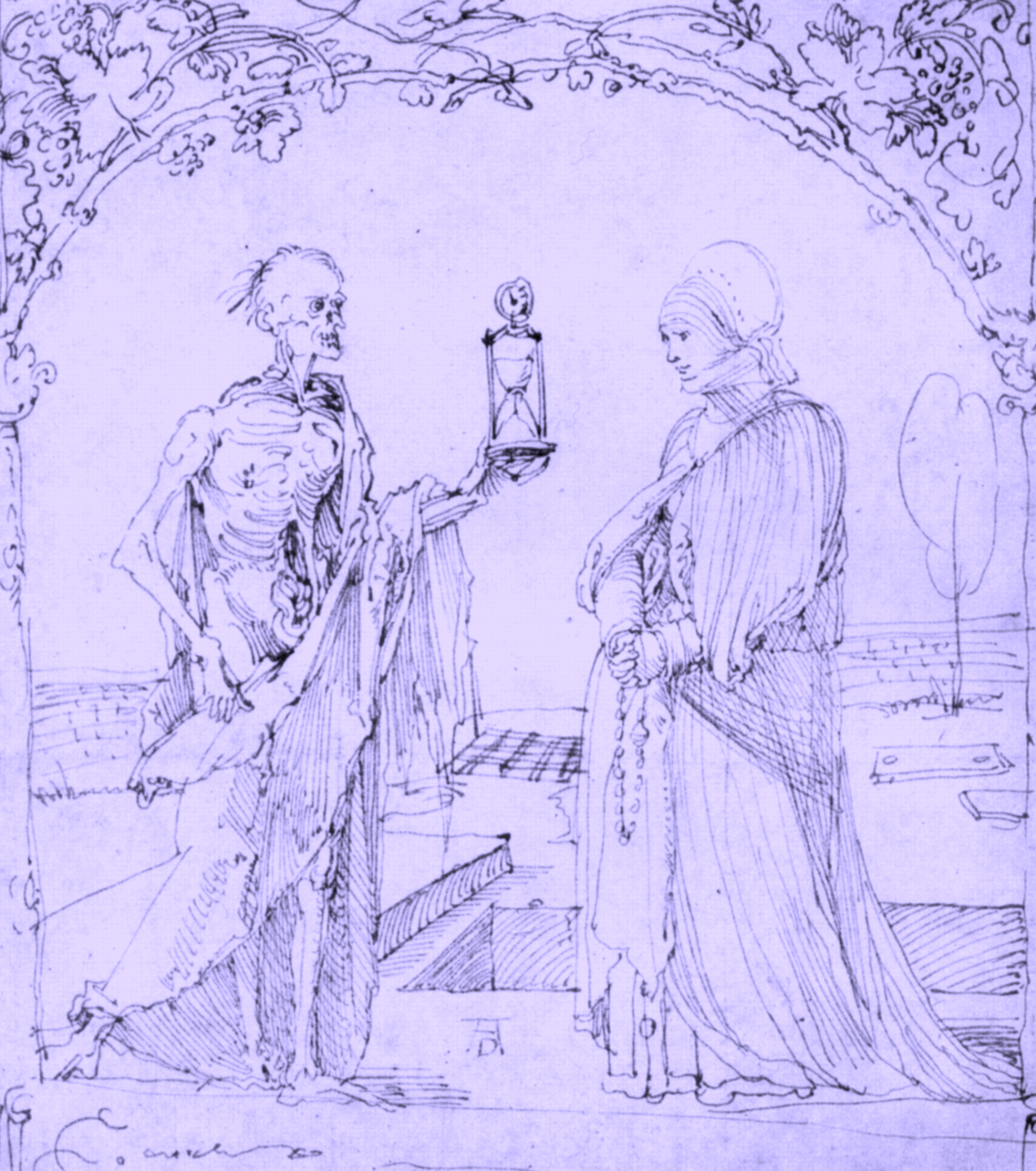

Images of a maiden caught or confronted or taken unaware by death, depicted as a skeleton, seem to have been everywhere in the Renaissance. All purport to remind us that beauty and youth are fleeting, that death awaits us and comes unbidden, at no predictable time. And all purport to place us in that half resigned, half regretful mood of Horace’s “Eheu fugaces, Postume, Postume /labuntur anni — Alas, Postumus, Postumus, how the years go fleeting by …”

Images of a maiden caught or confronted or taken unaware by death, depicted as a skeleton, seem to have been everywhere in the Renaissance. All purport to remind us that beauty and youth are fleeting, that death awaits us and comes unbidden, at no predictable time. And all purport to place us in that half resigned, half regretful mood of Horace’s “Eheu fugaces, Postume, Postume /labuntur anni — Alas, Postumus, Postumus, how the years go fleeting by …”

The taste of the whisky will turn grief into a fitting melancholy …..

The taste of the whisky will turn grief into a fitting melancholy ….. Peter Singer is much to be admired, for all the good he has done for animal rights and welfare. But he encountered much hostility, not for his naïve utilitarianism (let’s draw a veil, shall we?) but for his reasons for not eating animals. Some of the criticism in the German-speaking countries tended toward violence, even near riots in Austria. This was before the flowering of social media, but the internet was already spreading abuse of all sorts. Soon after Singer came to Princeton I came upon something on the web, an article ostensibly praising bestiality, advocating sex with animals, purporting to be by Peter Singer. and posted under his name.

Peter Singer is much to be admired, for all the good he has done for animal rights and welfare. But he encountered much hostility, not for his naïve utilitarianism (let’s draw a veil, shall we?) but for his reasons for not eating animals. Some of the criticism in the German-speaking countries tended toward violence, even near riots in Austria. This was before the flowering of social media, but the internet was already spreading abuse of all sorts. Soon after Singer came to Princeton I came upon something on the web, an article ostensibly praising bestiality, advocating sex with animals, purporting to be by Peter Singer. and posted under his name. was fertile ground for growing parody seems incontestable. As Goethe looks back so glowingly on his childhood, for example:

was fertile ground for growing parody seems incontestable. As Goethe looks back so glowingly on his childhood, for example: narrated in an equally glowing tone, always a bit overly so, by an amusing crook. Amusing in its own right, it is all the more so when reading Goethe alongside. Of course Mann raises the stakes: such passages as “Since that impassioned girl had cursed and sanctified my lips (for every consecration involves both)”

narrated in an equally glowing tone, always a bit overly so, by an amusing crook. Amusing in its own right, it is all the more so when reading Goethe alongside. Of course Mann raises the stakes: such passages as “Since that impassioned girl had cursed and sanctified my lips (for every consecration involves both)”  have as their counterparts passages considerably less inhibited. And the self-admiration is made just a touch more salient in Krull:

have as their counterparts passages considerably less inhibited. And the self-admiration is made just a touch more salient in Krull: Thomas Aquinas’ Five Ways were his five proofs of the existence of God, still taken seriously in the most traditional Thomist circles. In imitation thereof, pretending to be converted now to scientific realism, I wrote five proofs of the existence of unobservable entities, like electrons, quarks, or fields.

Thomas Aquinas’ Five Ways were his five proofs of the existence of God, still taken seriously in the most traditional Thomist circles. In imitation thereof, pretending to be converted now to scientific realism, I wrote five proofs of the existence of unobservable entities, like electrons, quarks, or fields.  Near the end of the week Jacques and Sara’s difficult relationship turns into a plan to go see the little horses of Tarquinia. The novel ends before they go. But if there is redemption gained in this story, it is through the project itself, through committing to this project to go see the little horses. Duras allows an insight to appear in one of the many voices around them: there are no holidays from love, you have to live it fully, boredom and all, you can’t take anything away from it.

Near the end of the week Jacques and Sara’s difficult relationship turns into a plan to go see the little horses of Tarquinia. The novel ends before they go. But if there is redemption gained in this story, it is through the project itself, through committing to this project to go see the little horses. Duras allows an insight to appear in one of the many voices around them: there are no holidays from love, you have to live it fully, boredom and all, you can’t take anything away from it.  We had a Michelin guide, which helped with the itinerary but gave little guidance to find non-Roman remains. And I remember a book, or perhaps several books, now quite lost, that gave directions not only to the famous necropoles but to Etruscan places in the countryside.

We had a Michelin guide, which helped with the itinerary but gave little guidance to find non-Roman remains. And I remember a book, or perhaps several books, now quite lost, that gave directions not only to the famous necropoles but to Etruscan places in the countryside.  I remember odd phrases, like “Ask for the custodian in the village — he is normally to be found on the bowling green”. And then the custodian would, sometimes a bit grumpily, fetch the key, unlock the door in what had looked like a small hill, let us in to the tomb. These small rural sites were not so spectacular but gave us the pleasant sense that, as itinerant but respectable vagrants, we were seeing much more than the usual visitors.

I remember odd phrases, like “Ask for the custodian in the village — he is normally to be found on the bowling green”. And then the custodian would, sometimes a bit grumpily, fetch the key, unlock the door in what had looked like a small hill, let us in to the tomb. These small rural sites were not so spectacular but gave us the pleasant sense that, as itinerant but respectable vagrants, we were seeing much more than the usual visitors.

her four-wheeled carriage and — surely this points to the aspects of life she cherished most? — her bronze bed.

her four-wheeled carriage and — surely this points to the aspects of life she cherished most? — her bronze bed. Katherine was on her way to spend the night in the fabulous if aging Chelsea Hotel, famed for its literati, suicides, a murder, and stories of spooky phenomena. The people she would meet there were ghost hunters, planning to detect any ghostly presence by scientific means. Exactly what would they do? She was not too sure yet, but one plan was to chart temperature differences in the room, during the night, using an infrared thermometer. Why would the thermometer be infrared, I wondered, was it to keep it from reflecting visible light? But no, I had misunderstood, this was a new kind of thermometer, still in beta stage, that used infrared light, it could just be pointed at someone to read their temperature. In fact, Katherine told me, all the technology ghost hunters used was digital, electronic, state of the art, the old devices did not work for them.

Katherine was on her way to spend the night in the fabulous if aging Chelsea Hotel, famed for its literati, suicides, a murder, and stories of spooky phenomena. The people she would meet there were ghost hunters, planning to detect any ghostly presence by scientific means. Exactly what would they do? She was not too sure yet, but one plan was to chart temperature differences in the room, during the night, using an infrared thermometer. Why would the thermometer be infrared, I wondered, was it to keep it from reflecting visible light? But no, I had misunderstood, this was a new kind of thermometer, still in beta stage, that used infrared light, it could just be pointed at someone to read their temperature. In fact, Katherine told me, all the technology ghost hunters used was digital, electronic, state of the art, the old devices did not work for them. But she had brought me a digital recording, made at midnight in the Princeton Cemetery, near the grave of Aaron Burr. It was not easy to make out … if it was a voice, it was someone repeating himself, upset that no one was listening, but I could not distinguish the words.

But she had brought me a digital recording, made at midnight in the Princeton Cemetery, near the grave of Aaron Burr. It was not easy to make out … if it was a voice, it was someone repeating himself, upset that no one was listening, but I could not distinguish the words.

Every year the Alpine Club publishes Accidents in North American Climbing. Just the facts, ma’am, straightforward reports from rangers and other climbers, data to reduce death and dismemberment to statistics. Free to the members, but it can be bought by anyone, pdf or print, very cheaply. The Club is missing a bet here, and a great source of funds! With all that prurient interest ready to be tapped …. Some gleeful writing about the silly mistakes, some bloody pictures too, and they’d make the New York Times best-seller list every time.

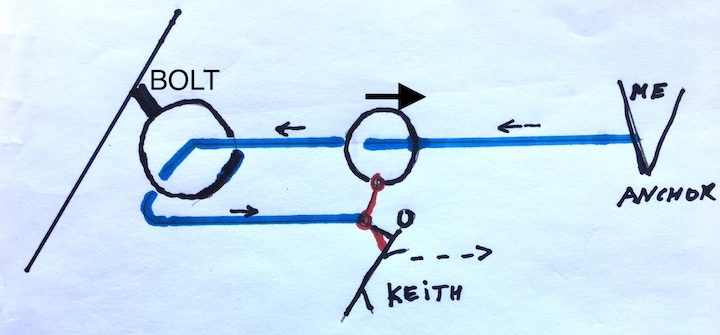

Every year the Alpine Club publishes Accidents in North American Climbing. Just the facts, ma’am, straightforward reports from rangers and other climbers, data to reduce death and dismemberment to statistics. Free to the members, but it can be bought by anyone, pdf or print, very cheaply. The Club is missing a bet here, and a great source of funds! With all that prurient interest ready to be tapped …. Some gleeful writing about the silly mistakes, some bloody pictures too, and they’d make the New York Times best-seller list every time. On the left side of this picture you see an obvious feature pointing up: its top is Hermaphodite Flake, and the blank part after that has several good bolted routes. One leads up and to the right: Eunuch (5.7R), the line I have drawn straight. The R stands for “Runout”, which means that some protection is scarily far apart. So Keith and I climbed up to Hermaphrodite Flake, crawled through underneath it, and turned to Eunuch.

On the left side of this picture you see an obvious feature pointing up: its top is Hermaphodite Flake, and the blank part after that has several good bolted routes. One leads up and to the right: Eunuch (5.7R), the line I have drawn straight. The R stands for “Runout”, which means that some protection is scarily far apart. So Keith and I climbed up to Hermaphrodite Flake, crawled through underneath it, and turned to Eunuch.

Mechanically it is a lot like the diagram for Keith’s set-up. The difference is that Keith could walk, while here you were hanging on the rope, your feet in two etriers (a sort of personal rope ladder), and had to use your jumars to pull yourself forward. And a thousand feet or so below you see the roof of the Ahwahnee hotel …

Mechanically it is a lot like the diagram for Keith’s set-up. The difference is that Keith could walk, while here you were hanging on the rope, your feet in two etriers (a sort of personal rope ladder), and had to use your jumars to pull yourself forward. And a thousand feet or so below you see the roof of the Ahwahnee hotel …

As we strolled through I walked with Calvino’s wife, Chichita, who talked with much feeling about some of the religious themes in the paintings. Realizing how much Calvino was ‘on the other side’, I exclaimed “Vous n’êtes pas chrétienne?”. But yes, she answered, and why not? I think she recognized my smile, there in communist Florence, among the literati of the left ….

As we strolled through I walked with Calvino’s wife, Chichita, who talked with much feeling about some of the religious themes in the paintings. Realizing how much Calvino was ‘on the other side’, I exclaimed “Vous n’êtes pas chrétienne?”. But yes, she answered, and why not? I think she recognized my smile, there in communist Florence, among the literati of the left ….  None of this is out of the ordinary, but it is extraordinary for me simply because I was, and am, so in awe of Calvino, of the way he writes, like a philosopher’s fantasy of a novelist.

None of this is out of the ordinary, but it is extraordinary for me simply because I was, and am, so in awe of Calvino, of the way he writes, like a philosopher’s fantasy of a novelist.  As I began to see, reading more of his writings, he also conceived of philosophical debate as no-quarter, no holds barred, hand-to-hand combat. But this was entirely at odds with how he dealt personally with us students: with old-fashioned courtesy and respect, even sympathy, though not exactly moderating his uncompromising critique. When eventually I had submitted my first dissertation chapter draft I received it back with red ink comments on virtually every line. In my memory, as I told him later, I would see myself going to his office up some stairs with a print of a snarling wildcat. Both he and his secretary denied adamantly that there had ever been such a print, which means, I suppose, that the memory was a symptom of PTSD.

As I began to see, reading more of his writings, he also conceived of philosophical debate as no-quarter, no holds barred, hand-to-hand combat. But this was entirely at odds with how he dealt personally with us students: with old-fashioned courtesy and respect, even sympathy, though not exactly moderating his uncompromising critique. When eventually I had submitted my first dissertation chapter draft I received it back with red ink comments on virtually every line. In my memory, as I told him later, I would see myself going to his office up some stairs with a print of a snarling wildcat. Both he and his secretary denied adamantly that there had ever been such a print, which means, I suppose, that the memory was a symptom of PTSD.

one of Popper’s followers, took the floor.

one of Popper’s followers, took the floor.