Last year I gave away my trad climbing gear, some of it new, some of it by then almost 25 years old. Not the end of the world: I would still be able to go sport climbing, where the bolts are all already installed, and of course continue in the climbing gym. And yet … I told Shelley and KP, climbers themselves, “there goes half my identity”.

Of all that I can relive in memory and imagination, what dominates is my sense of the rock. My rock paradigm: cool, smooth, hard, solid, something to trust with your life. Many a rock that does not instantiate this ideal. I’ve climbed on crumbling rock, exfoliation, with bits breaking off. I’ve sometimes stuck my pro in little cracks with edges like eggshells. I’ve slipped on basalt, God’s answer to stealth rubber. And still, pervasive in all my memory, is this sense of the rock I can trust, trust to bear me, to hold me, to offer me safety, to hold my feet on scarcely perceptible unevennesses, to carry me up.

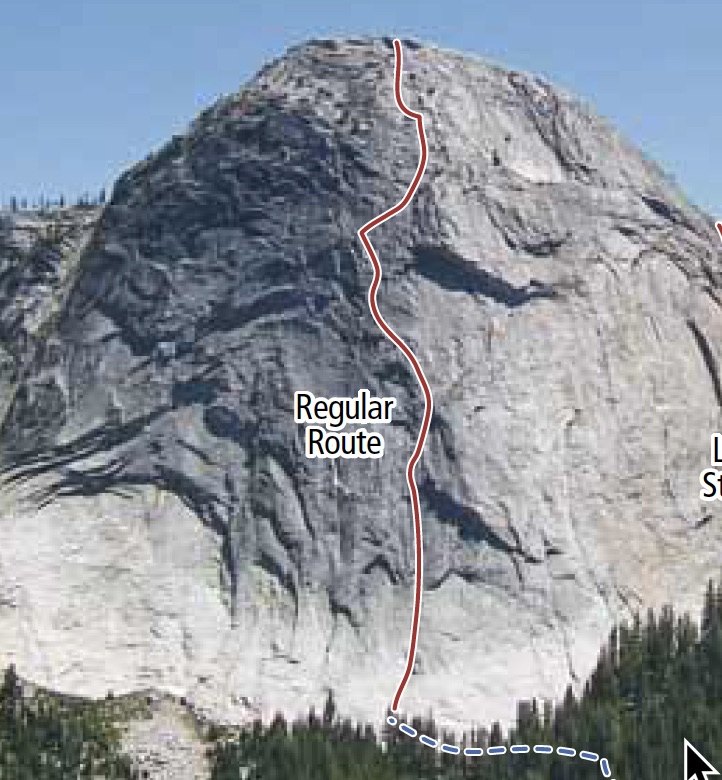

There is lots to remember, gratefully or ruefully, certainly fondly. When Ric Otte introduced me to Yosemite, I got hooked at once. But I did not lead during the first two years, just followed and belayed Ric and his friends … quaking in my climbing shoes as often as not. At the beginning of the third summer there, coming down from something harrowing –on Middle Cathedral, I think — I said “I don’t ever want to lead”.

They all understood it as a comment on how I had felt. Early the next morning they took me to the easiest climb in the Valley, Swan Slab Gully, and said “Lead!”.

Later, toward the end of that summer,  Ric told me, “look, you can follow 10a, so let’s go up Crest Jewel, you can lead the easy parts.” It was a good climb, lots of face and friction, but steep and rather dubious looking bolts. At some point, when he was leading a 10a pitch, he yelled down to me, “look, Bas, look at that helicopter flying down below us!”. I didn’t. I was swearing, “damn it, Ric! I don’t want to look down!”

Ric told me, “look, you can follow 10a, so let’s go up Crest Jewel, you can lead the easy parts.” It was a good climb, lots of face and friction, but steep and rather dubious looking bolts. At some point, when he was leading a 10a pitch, he yelled down to me, “look, Bas, look at that helicopter flying down below us!”. I didn’t. I was swearing, “damn it, Ric! I don’t want to look down!”

The first time I climbed Revival, in Church Bowl, I had the impression it was hardly ever climbed. About three-quarters on the way up, looking for protection, I found the remains of a bolt, not much more than a nail sticking out. I took an old wire-threaded nut, scrunched the wire around that rusty nail, prayed … Much later, on Hobbit Book in Tuolumne, I hung first a water bottle, and then one of my approach shoes, on bits of rock sticking out (‘dinner plates’ and ‘chicken heads’), to improvise some parody of bolt protection. These were not moments colored by fear, they stick in my memory with the felt satisfaction of cooperating with the rock, accepting what it let me have.

There is much else to climbing, of course. The easy together feeling of people who rely on each other; laughing over things that could have gone so badly … like when  Baylor and I vowed never again to rappel without adding a prusik safety ( a vow neither of us kept very faithfully).

Baylor and I vowed never again to rappel without adding a prusik safety ( a vow neither of us kept very faithfully).

And the minor miracles. Leading a pretty steep but not really difficult route in the Pinnacles, I suddenly found I could not move my left foot up. The little loop at the back of my climbing shoe had gotten caught in the carabiner clipped on the last bolt. Something, everyone said later, that had never before happened in the history of climbing.

And now I was not in a good position, right foot on a small hold, right hand stretched out above me — bending down was just not on. A controlled fall? No, I would pivot down from my caught left foot, slam into the rock, no way to fall free. Someone below told me to wait until they could go up farther on, and lower a rope to me. But could I stay in this awkward position so long?

A little miracle — I managed to worm my foot out of the shoe. Then I climbed up to the next bolt, on one shoe and one foot, secured myself, climbed down again to get the shoe. After climbing that day, I cut the loops on both shoes.

And once again, the rock I trust had held me in its loving arms, carried its tough love only as far as a warning.

It was around then that Dory Previn was singing

It was around then that Dory Previn was singing  .

.  The not -unconnected aftermath was the one million dollars endowment of the Pahlavi Shay of Iran Chair in Petroleum Engineering. Journalistic outrage noted that even President Roosevelt, paralyzed and confined to a wheelchair, had had to travel to USC in 1935 to receive his honorary doctorate. The news developed quickly. The Provost went into the hospital with a suspected heart attack and could not be reached for comments. President Hubbard had apparently already announced his plan to retire, some time beforehand, and was ready to do so now.

The not -unconnected aftermath was the one million dollars endowment of the Pahlavi Shay of Iran Chair in Petroleum Engineering. Journalistic outrage noted that even President Roosevelt, paralyzed and confined to a wheelchair, had had to travel to USC in 1935 to receive his honorary doctorate. The news developed quickly. The Provost went into the hospital with a suspected heart attack and could not be reached for comments. President Hubbard had apparently already announced his plan to retire, some time beforehand, and was ready to do so now. It reminded me at once of Pascal, who also lived in Paris, and whose work in mathematics is still remembered, some of it even so-named (‘Pascal’s triangle’). I know Pascal as a logician, as a mystic, as a romantic 17th century figure. But he was also the captive of the Jansenists of Port Royal, a Catholic group entirely Calvinist in its demeanor and tight-lipped constraint. From them he learned that mathematics is just another form of sexual self-indulgence. So he gave it up. Or tried … Eventually he allowed himself to engage in mathematics still, but only in time wasted with respect to the intellect: time spent in the bathroom.

It reminded me at once of Pascal, who also lived in Paris, and whose work in mathematics is still remembered, some of it even so-named (‘Pascal’s triangle’). I know Pascal as a logician, as a mystic, as a romantic 17th century figure. But he was also the captive of the Jansenists of Port Royal, a Catholic group entirely Calvinist in its demeanor and tight-lipped constraint. From them he learned that mathematics is just another form of sexual self-indulgence. So he gave it up. Or tried … Eventually he allowed himself to engage in mathematics still, but only in time wasted with respect to the intellect: time spent in the bathroom.  More tragically, there is the story of the logician, Leopold Loewenheim, originator of the Loewenheim-Skolem paradox (which I love inordinately much). The story is part of logicians’ folklore and may be apocryphal. What is true it that in the 1930s Loewenheim’s professional life as a high school teacher in Berlin came to an abrupt (though temporary) end, when he had to accept forced retirement as a 25 percent non-Aryan. Tarski visited him in that period, but after the war Tarski, like every one else, was convinced (wrongly) that Loewenheim had died in a Nazi concentration camp. It was during that time of rumors too, I think, that the story went about that Loewenheim had managed to continued doing logic in the camp, but only when he could hide in a bathroom.

More tragically, there is the story of the logician, Leopold Loewenheim, originator of the Loewenheim-Skolem paradox (which I love inordinately much). The story is part of logicians’ folklore and may be apocryphal. What is true it that in the 1930s Loewenheim’s professional life as a high school teacher in Berlin came to an abrupt (though temporary) end, when he had to accept forced retirement as a 25 percent non-Aryan. Tarski visited him in that period, but after the war Tarski, like every one else, was convinced (wrongly) that Loewenheim had died in a Nazi concentration camp. It was during that time of rumors too, I think, that the story went about that Loewenheim had managed to continued doing logic in the camp, but only when he could hide in a bathroom. Then, the next day he took us up a new route, and said that he would log it in at the climbing store as “Lolita” — a first ascent. I doubt he ever did. I was just as unreliable in my intentions — my notes in the back of Sebastian Knight were for a long story I meant to write about this time in Joshua Tree, and I never did.

Then, the next day he took us up a new route, and said that he would log it in at the climbing store as “Lolita” — a first ascent. I doubt he ever did. I was just as unreliable in my intentions — my notes in the back of Sebastian Knight were for a long story I meant to write about this time in Joshua Tree, and I never did.

The mass was celebrated by two priests, one young and one old. The young priest spoke Latin with such ease that he seemed to be talking with God as with a friendly neighbor (“hello God, it’s me, Damian …”, something like that) . The old priest was, in contrast, stumbling so much over the Latin, and so tardy, that the occasional coughing was growing slowly into a small epidemic. I was not Catholic, and not focused enough to overcome these barriers. I had hoped for something to intrigue me, that was not there.

The mass was celebrated by two priests, one young and one old. The young priest spoke Latin with such ease that he seemed to be talking with God as with a friendly neighbor (“hello God, it’s me, Damian …”, something like that) . The old priest was, in contrast, stumbling so much over the Latin, and so tardy, that the occasional coughing was growing slowly into a small epidemic. I was not Catholic, and not focused enough to overcome these barriers. I had hoped for something to intrigue me, that was not there. So I started going on Tuesday evenings. An apprentice monk would be in charge, give a little talk about breathing, counting our breaths up to 13, letting thoughts go their own way, as if they were birds flying by. Then we would sit. At first everything inside me was screaming to get out. After some weeks I had progressed to ten minutes of peace, before feeling as if a huge rock inside me wanted to roll out. At the end of twenty minutes we would have tea, and some desultory talking.

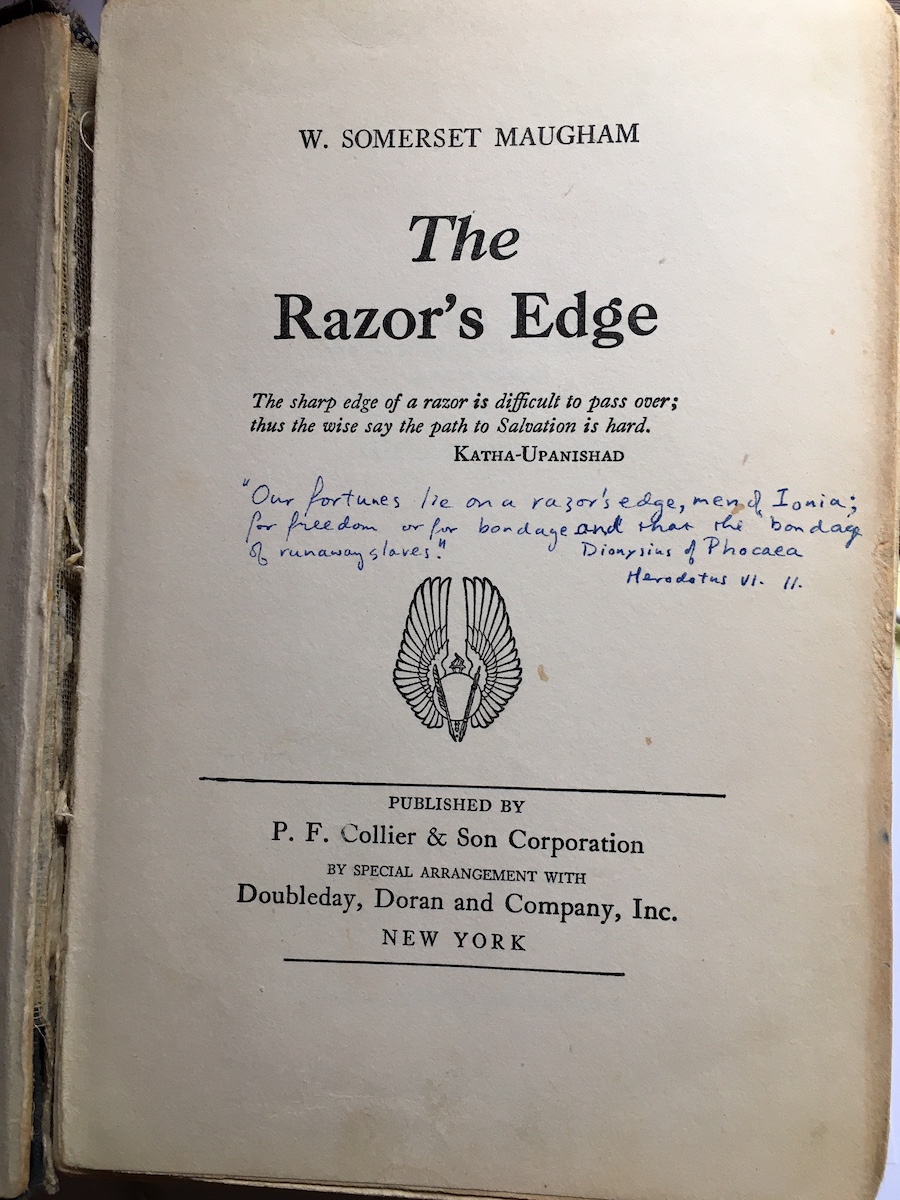

So I started going on Tuesday evenings. An apprentice monk would be in charge, give a little talk about breathing, counting our breaths up to 13, letting thoughts go their own way, as if they were birds flying by. Then we would sit. At first everything inside me was screaming to get out. After some weeks I had progressed to ten minutes of peace, before feeling as if a huge rock inside me wanted to roll out. At the end of twenty minutes we would have tea, and some desultory talking. The book’s title page has a quote from the Upanishads, “The sharp edge of a razor is difficult to pass over; … the path to Salvation is hard”. Underneath I wrote a quote from Herodotus, “Our fortunes lie on a razor’s edge …; for freedom or for bondage ….”. But Larry did not pass through sloughs of despond, his life was blessed, the razor’s edge was passed not in an upheaval but as growth.

The book’s title page has a quote from the Upanishads, “The sharp edge of a razor is difficult to pass over; … the path to Salvation is hard”. Underneath I wrote a quote from Herodotus, “Our fortunes lie on a razor’s edge …; for freedom or for bondage ….”. But Larry did not pass through sloughs of despond, his life was blessed, the razor’s edge was passed not in an upheaval but as growth.  Though this was some time after the sixties, it was still not so unusual for people to drop out, as they would say. She asked to be let out quite high up, at a track with not much to mark it. Before she stepped out, she asked when I thought I would be returning. About four hours later she was in fact waiting there in the same place to catch a ride back. I was rather intrigued, asked how she normally got about. “We live without money” she said, “we’re done with all that”. Very reluctantly she gave some vague answers. They had vegetables, they worked for food and other things, yes, she had been there for a few years now. For all she told me, she was a person with no past. I asked what the food might be like there out in the country. I’d be happy to treat her, if she wanted to stop for a meal. When we were in the cafe she told me to have a dish, which turned out to be very plain, just plantains, rice, and beans. “I don’t want anything to eat”, she said, “but if it is ok I would like a glass of wine”. It sounded like a concession, something that would be obtained with money. With her reluctance to talk so obvious, I found myself tongue-tied. Having dropped out, was she free, free from a bondage that characterized my own life? A freedom that was in any way like what Larry had sought? I could not find a good way to ask it.

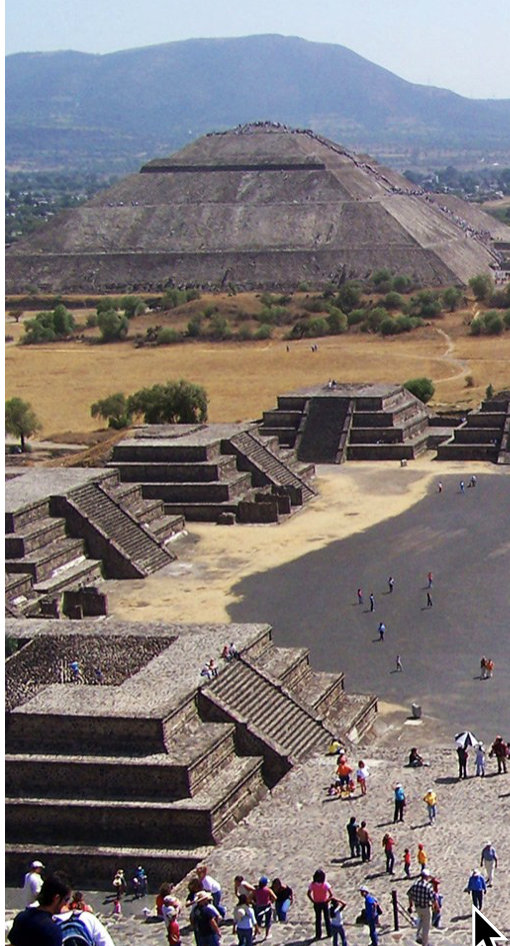

Though this was some time after the sixties, it was still not so unusual for people to drop out, as they would say. She asked to be let out quite high up, at a track with not much to mark it. Before she stepped out, she asked when I thought I would be returning. About four hours later she was in fact waiting there in the same place to catch a ride back. I was rather intrigued, asked how she normally got about. “We live without money” she said, “we’re done with all that”. Very reluctantly she gave some vague answers. They had vegetables, they worked for food and other things, yes, she had been there for a few years now. For all she told me, she was a person with no past. I asked what the food might be like there out in the country. I’d be happy to treat her, if she wanted to stop for a meal. When we were in the cafe she told me to have a dish, which turned out to be very plain, just plantains, rice, and beans. “I don’t want anything to eat”, she said, “but if it is ok I would like a glass of wine”. It sounded like a concession, something that would be obtained with money. With her reluctance to talk so obvious, I found myself tongue-tied. Having dropped out, was she free, free from a bondage that characterized my own life? A freedom that was in any way like what Larry had sought? I could not find a good way to ask it.  In the years around 1980 I went three times to Mexico City: for a lecture, for a four-week seminar, and for a conference up in the mountains to honor Hilary Putnam. It was on the first occasion that I took an extra week to explore the city. On the first day I went out to the Teotihuacan Pyramids north of the city. After a while, rather tired, I sat down on the steps of one of the smaller pyramids near the Pyramid of the Moon, close to a couple that I had seen sitting there for a while. The man, distinctive because he was wearing two hats one on top of the other, had been sketching. He called over, sounding American, and asked if I’d like half a sandwich? I said I had brought some snacks, but could I look at what he had been drawing?

In the years around 1980 I went three times to Mexico City: for a lecture, for a four-week seminar, and for a conference up in the mountains to honor Hilary Putnam. It was on the first occasion that I took an extra week to explore the city. On the first day I went out to the Teotihuacan Pyramids north of the city. After a while, rather tired, I sat down on the steps of one of the smaller pyramids near the Pyramid of the Moon, close to a couple that I had seen sitting there for a while. The man, distinctive because he was wearing two hats one on top of the other, had been sketching. He called over, sounding American, and asked if I’d like half a sandwich? I said I had brought some snacks, but could I look at what he had been drawing?  For Robin Kornman I have to go back again, to the summer of 1969, when I taught a short course on Existentialism, in Bloomingon, Indiana. That was a hippy summer, awash in marijuana, flute playing, reading from the Tibetan book of the Dead, all that sort of thing. The students — another of whom, Steven, would become a Buddhist teacher, and I would eventually know well — tended to approach Sartre’s Being and Nothingness as a sacred text. What struck me about Robin was that he seemed so sensual, as if he were tasting the words.

For Robin Kornman I have to go back again, to the summer of 1969, when I taught a short course on Existentialism, in Bloomingon, Indiana. That was a hippy summer, awash in marijuana, flute playing, reading from the Tibetan book of the Dead, all that sort of thing. The students — another of whom, Steven, would become a Buddhist teacher, and I would eventually know well — tended to approach Sartre’s Being and Nothingness as a sacred text. What struck me about Robin was that he seemed so sensual, as if he were tasting the words. But Robin, who died at age 60, is much alive on the web, presenting many spiritual teachings, and recalled in fond remembrances by other Buddhist initiates. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche is easily found there too, named by a group of fifty women who accuse him and his acolytes of sexual abuse.

But Robin, who died at age 60, is much alive on the web, presenting many spiritual teachings, and recalled in fond remembrances by other Buddhist initiates. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche is easily found there too, named by a group of fifty women who accuse him and his acolytes of sexual abuse. At that time belly-dancing was salient in women’s liberation, a rebellion against male chauvinist constraints on free expression. Driving north on the coastal highway I would pass long, low, soft hills, the eucalyptus trees at the bottom studded in places with broken hang-gliders. In Santa Barbara I would drive past the mission into the eastern hills where my friends lived, a place of hot tubs and hummingbirds.

At that time belly-dancing was salient in women’s liberation, a rebellion against male chauvinist constraints on free expression. Driving north on the coastal highway I would pass long, low, soft hills, the eucalyptus trees at the bottom studded in places with broken hang-gliders. In Santa Barbara I would drive past the mission into the eastern hills where my friends lived, a place of hot tubs and hummingbirds.  Native Californians often have an unconscious moral high tone, likely to sound somewhat self-righteous to others, reflecting a conviction that they already exemplify their new-age ideals. Looking back to that time I do not cease to admire the ideals, or the moral fervor exhibited by the Beats, the Hippies, the folksingers that everyone loved, … but I can also see that consciousness-raising was, by their own lights, at best gradual.

Native Californians often have an unconscious moral high tone, likely to sound somewhat self-righteous to others, reflecting a conviction that they already exemplify their new-age ideals. Looking back to that time I do not cease to admire the ideals, or the moral fervor exhibited by the Beats, the Hippies, the folksingers that everyone loved, … but I can also see that consciousness-raising was, by their own lights, at best gradual.  Nevertheless we stuck to the plan for the next day, to climb Fairview Dome. Ric and Dan took charge of me. The others made up a second party. When they had climbed a pitch, though, Jim had too much of a headache, and they went back to camp. It is a wonder, in retrospect, that Ric and Dan managed to get me up all those pitches, and I was slowing them down considerably. We also hadn’t left early. Much of our conversation was about the peach milkshakes to be had in Curry Village once we got down, whether we would meet the others there in the pizza place … bit by bit the talk turned from what we would eat to whether we would get there in time, and then to whether we would be walking down in the dark ….

Nevertheless we stuck to the plan for the next day, to climb Fairview Dome. Ric and Dan took charge of me. The others made up a second party. When they had climbed a pitch, though, Jim had too much of a headache, and they went back to camp. It is a wonder, in retrospect, that Ric and Dan managed to get me up all those pitches, and I was slowing them down considerably. We also hadn’t left early. Much of our conversation was about the peach milkshakes to be had in Curry Village once we got down, whether we would meet the others there in the pizza place … bit by bit the talk turned from what we would eat to whether we would get there in time, and then to whether we would be walking down in the dark …. There are many, many climbing stories to be told, from the next twenty-five years, but for now I just want to touch on life in Camp Four. It is a very lively, but in itself truly lugubrious place, with a single bathroom, a few water taps for an awful lot of people. But there is a picnic table and bear boxes for each site. No showers, but Ric found a key to the outdoor showers belonging to the Yosemite Lodge across the road, and those we enjoyed until, a few years later, a flood took out that entire area.

There are many, many climbing stories to be told, from the next twenty-five years, but for now I just want to touch on life in Camp Four. It is a very lively, but in itself truly lugubrious place, with a single bathroom, a few water taps for an awful lot of people. But there is a picnic table and bear boxes for each site. No showers, but Ric found a key to the outdoor showers belonging to the Yosemite Lodge across the road, and those we enjoyed until, a few years later, a flood took out that entire area.  Eco was a big man with a big personality. I think it was in 1984 that he spent a longer time in New York, at Columbia University. One evening after dinner I walked back with him to his apartment in the West Village. On one street he suddenly stopped, in front of a window display of a crystal ball. “Let’s have our palms read!”

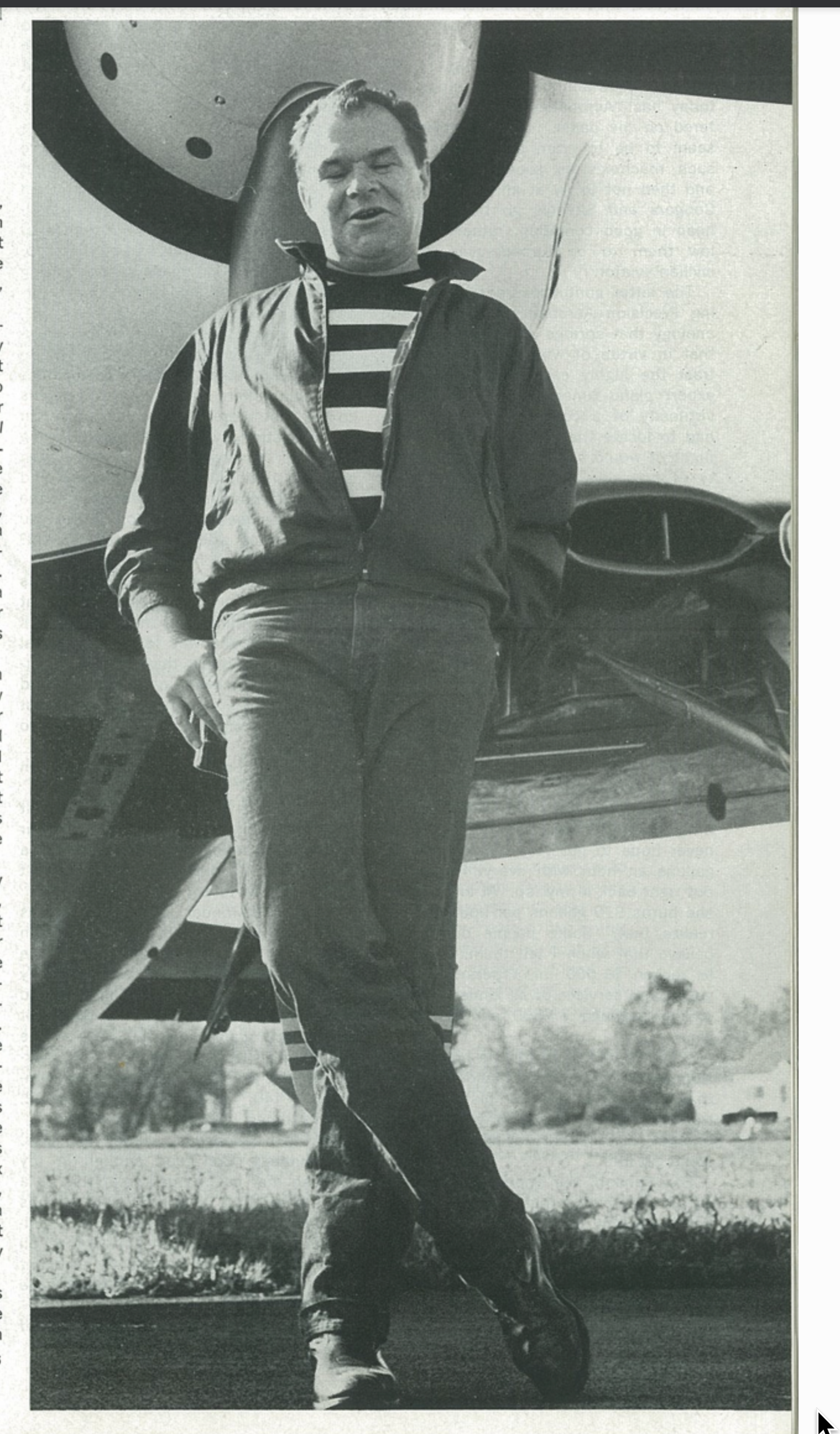

Eco was a big man with a big personality. I think it was in 1984 that he spent a longer time in New York, at Columbia University. One evening after dinner I walked back with him to his apartment in the West Village. On one street he suddenly stopped, in front of a window display of a crystal ball. “Let’s have our palms read!”  When I came to Yale, fresh out of graduate school in 1966, they assigned me an office next to Hanson’s, on the 3rd floor of a smallish building, Connecticut Hall. It was an idyllic time for me, with free time, seclusion up there in the attic, and good friends. On sunny days I would sometimes climb out of the window to eat my lunch on the roof, like the people in Frayn’s Landing on the Sun. It was a while before I had much contact with Hanson, who seemed always to be traveling, whether to lecture or to fly his Bearcat, a World War Two fighter plane. So to begin there were just the stories, how he had challenged the university over a tenure case by flying over the Yale Bowl to drop leaflets, how he had come unscathed out of a lawsuit through expert testimony that the witnesses could not tell whether he was flying just ten feet above the golf course … or farther back, that as a Marine fighter pilot he had been grounded for looping the loop around the Golden Gate bridge.

When I came to Yale, fresh out of graduate school in 1966, they assigned me an office next to Hanson’s, on the 3rd floor of a smallish building, Connecticut Hall. It was an idyllic time for me, with free time, seclusion up there in the attic, and good friends. On sunny days I would sometimes climb out of the window to eat my lunch on the roof, like the people in Frayn’s Landing on the Sun. It was a while before I had much contact with Hanson, who seemed always to be traveling, whether to lecture or to fly his Bearcat, a World War Two fighter plane. So to begin there were just the stories, how he had challenged the university over a tenure case by flying over the Yale Bowl to drop leaflets, how he had come unscathed out of a lawsuit through expert testimony that the witnesses could not tell whether he was flying just ten feet above the golf course … or farther back, that as a Marine fighter pilot he had been grounded for looping the loop around the Golden Gate bridge. But he materialized soon enough: the few of us in logic and philosophy of science had a little reading club in Danny’s, Charles Daniels’, rooms. When Hanson walked in it was less like a human entrance than like a theater’s scene change — he filled the room with both mind and body.

But he materialized soon enough: the few of us in logic and philosophy of science had a little reading club in Danny’s, Charles Daniels’, rooms. When Hanson walked in it was less like a human entrance than like a theater’s scene change — he filled the room with both mind and body.  j

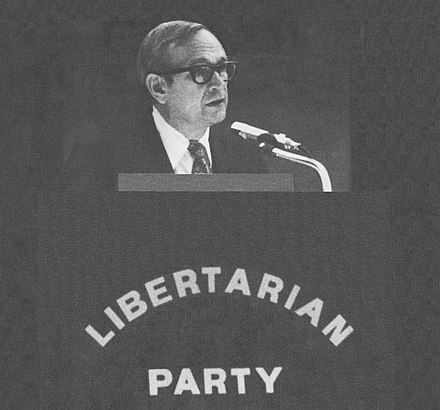

j Bishop Fulton J. Sheen

Bishop Fulton J. Sheen  Now I know that this man, the voice of orthodox Catholicism, was the prime Christian anti-Communist crusader in America for some thirty years. But what a speaker! Think of the efficacy of this technique:

Now I know that this man, the voice of orthodox Catholicism, was the prime Christian anti-Communist crusader in America for some thirty years. But what a speaker! Think of the efficacy of this technique:  Paul Feyerabend

Paul Feyerabend

Certainly, Scriven had dramatic presence on stage. But it paled to insignificance, in my view, when Buckley stood up. With his patrician New England accent, his seemingly choreographed body language as he spoke, his Shakespearean fluency, he projected not simply his own image but the image of a world. Buckley’s logic and rigor could distract you from his unspoken premises, and his conclusion he would throw away, as it were, just turning away from the audience to cast it as an aside … I had never, and would never again, see such debating skill.

Certainly, Scriven had dramatic presence on stage. But it paled to insignificance, in my view, when Buckley stood up. With his patrician New England accent, his seemingly choreographed body language as he spoke, his Shakespearean fluency, he projected not simply his own image but the image of a world. Buckley’s logic and rigor could distract you from his unspoken premises, and his conclusion he would throw away, as it were, just turning away from the audience to cast it as an aside … I had never, and would never again, see such debating skill.