The Slav-Makedon

In the spring of 1976 I was in Greece, and about to go north from Athens. I wondered if I could go to the peninsula of Mount Athos, the independent monastic region.

Not too easy! The region is under the protection of the Greek state, which safeguards its special dispensation. First the Canadian consulate had to give me a document certifying that I was a Canadian citizen in good standing, and male. No women, nor even any female animals, are allowed on Athos. This document I duly took to the Ministry of the Exterior, where I received a permit to cross into Athos, an imposing document with some amazing looking stamps.

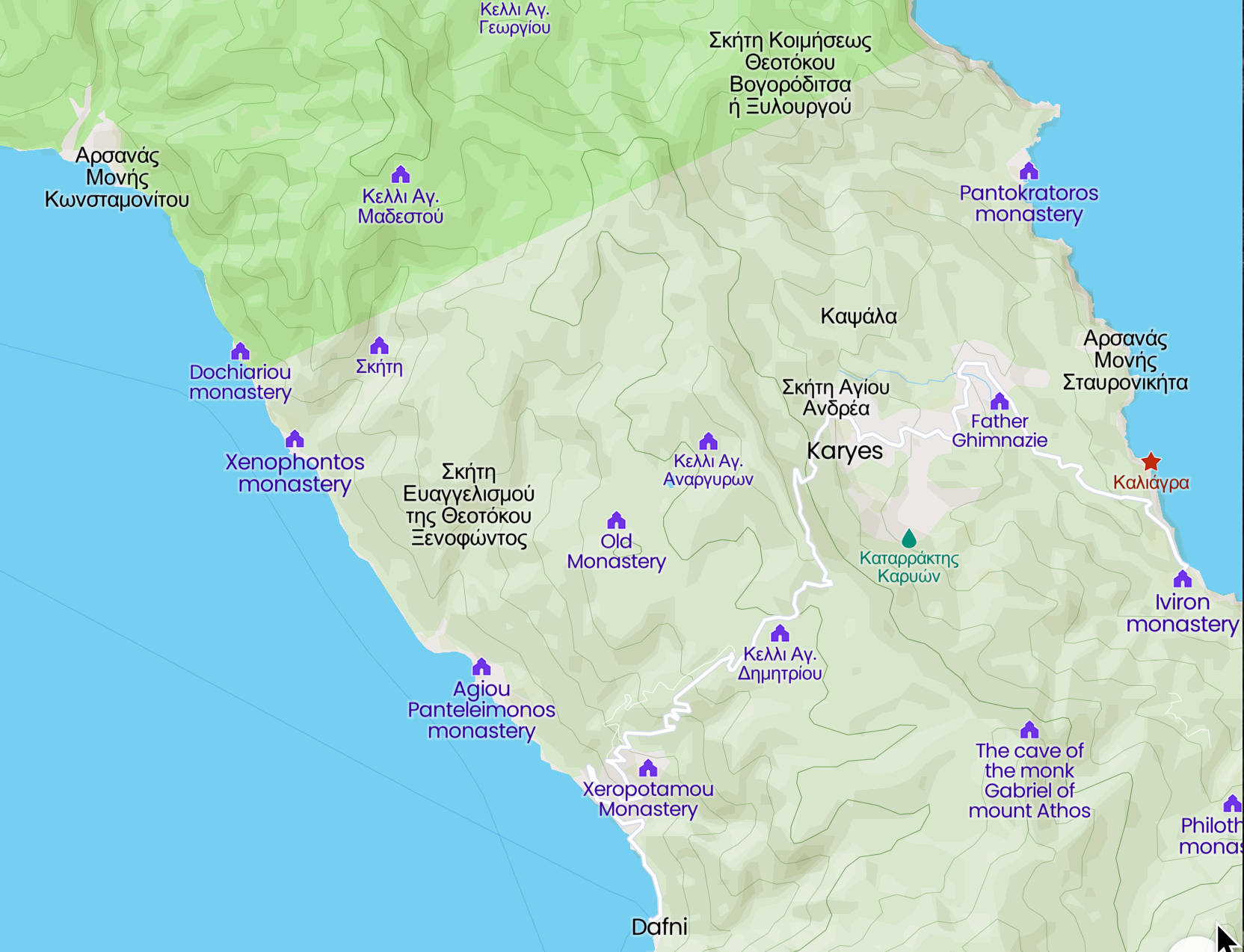

Looking through old notebooks recently, I found a sort of diary from when I was there. The map and photos I’ve supplied now from the web — everything looks in better repair now than it did some forty years ago.

Karyes = Karie

Karyes = Karie

Thursday, April 17, 5 PM, in the bus from Thessaloniki. The lady beside me was ill the whole way. It made her hiccup, but not embarrassed. At first I thought she had known it would happen and had prudently dressed all in black for it. But as we neared Stagira (birthplace of the Stagirite, with statue to prove it) black became the predominant color. So did the outward signs of religion, if not of grace; shrines and chapels everywhere, just large enough for the weary to sit down and pray. We arrived in Ouranopoulis, on the coast, at 9:15 and I got a bed in a three-bed room. The rain had started again, and the town, bathed by the Aegean from the south and by washed-out lamp light from above, sank reluctantly into the night. The little hotel creaked and snored and shivered gently in the wind.

Friday, April 18, 6:30 AM. Asceticism begins here. Breakfast is Greek coffee and a chunk of dry bread. We get on a motorboat, which chugs up the coast in a alert sort of way, not shared by anyone on board. But there are foreigners besides me. A busy-body German who waves goodbye to his wife with a guaranteed long lasting smile; a couple of hairy Americans of the hip-but-heavy sort; and some German Wandervögel, dressed in plus-fours and knee-sox. I want to walk alone, I decide to lose sight of them as soon as possible.

I must shake off this misanthropy.

Friday, mid morning. We stop at the monastery of Xenophontos to pick up a jolly grey old priest with a tense monk. They come along to Daphne, and buy octopuses from the boatsmen when we land. Form the port of Daphne a bus takes us along their one and only motor road, to Karie. The views are breathtaking and so is the driving; each bend is taken in first gear, but without slowing down. In Karie we must first obtain police permits; then bring those with our papers to the Palace of the Holy Supervision. There we receive the Diamonitrion, the last and final permit.

By this time I have decided against any itinerary that brings me back to Karie, or involves the bus, or, to begin at least, the presence of humans with or without mules. The girly magazine on the policeman’s desk was the last straw. I find a restaurant where they have two kinds of soup, and bread and water. By now I am very hungry, all of it tastes like nectar and ambrosia to me. It is twelve o’clock. A shop keeper and a monk convince me, which much miming off wild boar and lack of signposts, not to set off for Monastery Konstamido.

Friday, noon. Instead then I start in the direction of Monastery Khirapotamou. To begin the area is very cultivated, then the path goes into the woods. I am anxious to branch off from the main road, to walk alone. Too anxious perhaps; at one-thirty I am at a crossing I cannot place it on the map. But the walking has been good. I have seen dung beatles just like Doris Lessing describes: two of them rolling a bit of dung uphill, and then rolling helter-skelter after it. And flies with long legs, flying like storks.

From the highest ridge I could see the sea on the north, and Karie and monasteries and retreats spread out in a giant fan. But I am probably lost. Just then a very small man in sneakers and a squashed gray fez shows up. He is going toward Khirapotamou, and walks ahead over a special shortcut. Frequented only by his tame rabbits and him, I’ll swear, unless there are more of these gnomes. Perhaps he lives at the fork just for wayward hikers like me. About two o’clock we are on a high ridge, and the monastery appears below. I thank him and rest a while, with bites of the restaurant bread I had saved, and sips of retsina. I go down through a perfectly lyrical gorge, and see the little man perching in a farm building. At the monastery I do not go in, I am feeling restless, and set off at once in the direction of Monastery Panteleimon.

Friday midafternoon. There is an official path according to map, but somehow I miss it. I’m going cross country, following the sort of paths mules disdain. This is medieval land — the touch of human hands everywhere, the paths clear and worn. Whoever walks here doesn’t come with foreign objects, concrete, steel, or asphalt. A bit after 4 o’clock, I sit on a rock with my bare feet dangling in the sea. Cannot swim! Men in shorts are expelled.

5:00 Friday. I reach Panteleimon.. The buildings rise up like man-made cliffs. There are three huge four-story buildings by the sea and a bit behind them, the monastery proper. It is like a little city, but a dying one. No single building is in good repair; paint is peeling, windows are broken, roofs are falling in. The monastery can be entered only by the main gate, solid wood and iron, tons heavy. There is no one. I push the door open, walk into the courtyard. I am dwarfed by the cliff-like walls and towers all around, and by the silence.

There is a fountain with no water; two gongs, one of rusted iron, one of wood. There is no one. Hesitantly I walk on, through corridors that lead nowhere. Through one window I see an eating hall, as in a college, with seating for hundreds. Through another window, religious paintings. One corridor finally brings me to human noise; a kitchen. A solitary cook stands working between a great fire and a mammoth iron pot of green beans. I knock, but he does not hear. I turn a corner, and find an old gray beard, sitting on stool with a cigarette, the picture of dejection, frozen in body and in spirit. ” Kale sphera!” I say. “Germania?” “Ochi, Kanada” I reply. The eye descends again, but past the cigarette, which falls to pieces between strengthless fingers. I go back to the cook, and catch his attention. He gestures irritably. I walk out, back through the courtyard and the gate, to sit on the outside steps, and read.

7:45 pm Friday. There was no sign of life still about six, then a laborer directed me to one of the three large buildings by the sea. It seems deserted too, but I wandered its corridors till I found a monk. He showed me a small room with a bed, and gave me food: lentil soup, bread, and water. I read for a while, then I go out.

In the gardens there is a huge monk, pacing the walk, playing with his beads, and taking the odd gargantuan sniff of a pink rose. I don’t want to disturb his meditation … but he notices me and comes over. “I speak English”, he announces. This is the Slav-Makedon. I call him that in my mind, since he describes himself so repeatedly. By nationality he is Greek, from the North Western part, Greek Macedonia. He tells me that this monastery is Russian, and that he has learned his English from a book without teacher (but surely he must have learned the pronunciation in a different way?)

At present the fathers are asleep, he says; they will awake at midnight for a liturgy lasting till dawn. Walking with me he shows me the great hall, we go to stand inside it. The next morning I will be able to see the church. But now I must go in. The monastery closes at 8:15, so does the guesthouse. I return to my room and the monk who takes care of guests lights my oil lamp. Tomorrow I plan to walk all the way to Monastery Kostamitou.

Saturday. I am ill. I spend the whole day in bed, with well-meaning interruptions every two hours. I get weak tea and bread. The Slav-Makedon brings me an orange and an aspirin at noon, and I realize from the special care that an aspirin is valuable here. He tells me his life story. He was a poor boy, in the Communist part of the country during the Civil War. When he was about fifteen the Communists lost. It was like Vietnam, he says, with planes bombing his village . Some years later he did his stint in the military, then was ordained a Deacon. He finished high school in Karie five years ago, when he was thirty. But under the dictatorship he could not get a passport to go study in France as he wished. Greek communities do not wish him as Deacon, as his native language is a Slav dialect. He thinks, though, that if he stays in this Russian monastery for two years he will get a testimonial, and perhaps he can get a post abroad.

As he is telling me this plan, his sense of the difficulties overwhelms him. “I am a very poor man, I was always poor.” He turns his face away, and smites his brow. “I have not had good luck, born a Slav-Makedon.”

In the evening I have some soup again, potatoes and mint soup. The Slav-Makedon returns and brings me something that looks like houmous and bread. I start eating it, and like it rather. He explains he has made it himself of oil, onions, and the eggs from the belly of a fish. It’s called Dharama-salata. I finish almost all of it. He sits down heavily. In appearance the Slav-Makedon is a heavy-set fellow, looking ten years older than his actual thirty-five, with large black gray beard and balding forehead. He is reflecting, perhaps my coming has made him reflect more on his situation, or more sadly. He says “I am still a khoungk man, I do not like to stay in the monasteries”.

Sunday morning. I have weak tea, and feel better, though still a bit weak. I shall stay here this morning to see the church, and in the afternoon walk for only one or two hours. About 8:30 in the morning I enter the monastery gate and one of the caretakers leads me up interminable stairs, deep into the cliff of buildings, to a great church. The audience slowly grows, bu t remains small, consisting of me, some monks and laborers. There were about eight monks present altogether.

Diagram. Here I stand and sometimes sit in the tall chair marked X. The circle marks the dome with skylights, and a giant chandelier. The wall that separates us from the priests is all gilt with large paintings and ikons. The shadowed part is a trellis door.

The service was already going on and last two more hours, choreographed in the minutest detail. First I was only aware of the chanters, the fathers. Then I heard a chanted reply from behind gilt wall; I realized that was a trellis in it, for I saw candles moving behind it. Then the trellis was opened, it was a giant door, and the priest appeared. He was dressed in grand purple and gold robes, bare-headed, blond and youngish; attention totally withdrawn even when he came near us with the incense swinger to greet us each with a ceremonial nod; parchment-white skin drawn tautly over fine bones.

Major parts of ceremony were marked by the opening or closing of the gilt doors, and twice by the drawing of a red (scarlet or vermilion, the light was dim; at least, not purple) curtain behind the gilt. The priest would bear the objects forward: a book, two chalices covered with purple and brocade, a cross — sometimes he was followed by a monk with a candle in a giant holder. The service ended with communion, which involved only bread and no wine. The bread was carried around, and I was encouraged to partake, it was rather like a hospitable offering of bread all around, more friendly than solemn.

The Slav-Makedon, who had been one of the chanters now showed me various paintings. One was done almost entirely in white gold, of the holy family; one a Madonna and Child with many blue jewels; one of St. Pantoleimon, whose eyes were focused on me whether I stood far and to the side, or close and below; one with small pictures, one for each day of the year. We walked down the stairs to the courtyard, and I was invited to eat with them. When I say “we” here, I mean the laborers and a couple of deacons, not the priest or fathers, who had stayed behind. I sat in the sun for five minutes feeling weak.

We went in, the Slav-Makedon and I, and he pointed me to my place. This was the great eating hall. An old monk, another monk, the deacon, the Slav-Makedon, and I each sat at the head of a different almost empty table with room for fifty. We sat before our food, waiting. Then the priest entered, now in black, with three chanting monks; he bore a candle to its place, and the old monk got up and began to read scriptures. The little group went to sit with the Slav-Makedon, and the priest rang a bell. Then we ate. The food was a chick-pea soup (of which I ate the solid part), bread, water, wine (one sip; it was strong and harsh), fish gruel (I ate none, wisely). There was no chatting; this was part of the ceremony, and when the priest had rung the bell for the third time, we filed out, to another church, across from the eating hall.

I stayed only a little while; then I left at and packed. At quarter to twelve I started walking to Xenophontos, hearing the great bell behind me.

Sunday afternoon. I have made up my mind to go back tomorrow morning. The idea cheers me up a lot, actually, for I am still not feeling very well. I am walking like an old man, through a beautifully sunny countryside. My senses are turning inward, it needs an effort to look up. But slowly my headache disappears, and my stomach stabilizes. I walk very slowly, and of course, meet no one.

About halfway along I come upon a large two-story house, by well tended meadows. It is deserted; the door has been taken off, and five bulls live inside. They come out one by one, bells clinking, and stare at me with arrogant curiosity. Their evident aristocracy reminds me of the Russian priest officiating intensely seriously at the ceremonies, daily, oblivious of the decay of his monastic city. Somewhat farther still a small stream rushes across the path, and falls clattering into the gorge below. There are smooth rocks around it, and I lie down, on my rucksack, to doze in the sun. I could sleep in this sunny day forever. But I do go on; and Xenophontos appears.

It is much smaller than St. Panteleimon, though still a large complex. The outbuildings are also dilapidated, but once I pass in through the gate, everything is very well kept, painted, repaired. There are monks going about their mysterious business, and well-cultivated areas of land below the walls. The monks offer me coffee, but I beg tea; it comes strong and sugary. I feel much better. I doze in the sun, and even write some parts of these notes. Except for giving me tea, and answering my questions about the boat, the monks leave me totally alone.

I was happy to see some signs of age and creeping destruction here and there, as I wandered around, for so far Xenophontos had looked like a Swiss Farm compared to Panteleimon. There is a great noise off bells and gongs from time to time. Also great periods of quiet; but it is a well-tended quiet, not the desolation of the Russian monastery.

Monday early morning. I wandered away yesterday, and missed the meal, which must be earlier here than in Panteleimon. But when they realize it, the monks made a great to do (they came upon me reading in the lounge) and took me to the cook. He brought me a heaping plate of potatoes in a sauce of mint and spices, in a smallish dining room (designed for about forty or fifty, say). The wall was covered all around by murals of saints and monks, the dominating color black, and the colors were fading badly.

The boat is waiting.

Today Saint Sara the Egyptian is worshiped by the Roma, annually at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, and they carry her statue into the sea. The Bishop comes to give his blessing although, just as in the case of St. Christopher, the Church does not recognize her as a saint.

Today Saint Sara the Egyptian is worshiped by the Roma, annually at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, and they carry her statue into the sea. The Bishop comes to give his blessing although, just as in the case of St. Christopher, the Church does not recognize her as a saint.  I heard about her when visiting the Abbey of San Michele near Torino. The care-taker monk told me the legend. It happened in a time of war, but there were so many wars, skirmishes, raids, sieges. Ruins of forts and castles are strewn everywhere across this region. Ada was a young woman in a village near the Abbey. When the soldiers came all the villagers rushed to the Abbey for shelter, but the enemy was on their heels. Pursued by the mercenaries, Ada fled to the top of the monastery’s outer tower. She heard the soldiers’ boots on the stairs behind her, there was nowhere to go. Commanding her life to the care of San Michele, she leaped off. There was a miracle. Miraculously unhurt, she escaped to safety.

I heard about her when visiting the Abbey of San Michele near Torino. The care-taker monk told me the legend. It happened in a time of war, but there were so many wars, skirmishes, raids, sieges. Ruins of forts and castles are strewn everywhere across this region. Ada was a young woman in a village near the Abbey. When the soldiers came all the villagers rushed to the Abbey for shelter, but the enemy was on their heels. Pursued by the mercenaries, Ada fled to the top of the monastery’s outer tower. She heard the soldiers’ boots on the stairs behind her, there was nowhere to go. Commanding her life to the care of San Michele, she leaped off. There was a miracle. Miraculously unhurt, she escaped to safety.  Since it ceased to be a dormitory for Princeton’s gentlemen students and their servants, the eastern half of 1879 Hall houses Philosophy, while its western half has Religion. The two are separated by a imposing, not to say intimidating, archway. Above the arch Woodrow Wilson had his office, till the alumni got rid of him for wanting to interfere with the eating clubs. It has a fireplace large enough to roast lambs, and was given to Philosophy for its faculty meetings, social gatherings, and — during some years rather out of the ordinary — raucous parties. And then, in 1992, came the announcement that there was to be a grafting-on of a new and modern space, for a Center for Human Values.

Since it ceased to be a dormitory for Princeton’s gentlemen students and their servants, the eastern half of 1879 Hall houses Philosophy, while its western half has Religion. The two are separated by a imposing, not to say intimidating, archway. Above the arch Woodrow Wilson had his office, till the alumni got rid of him for wanting to interfere with the eating clubs. It has a fireplace large enough to roast lambs, and was given to Philosophy for its faculty meetings, social gatherings, and — during some years rather out of the ordinary — raucous parties. And then, in 1992, came the announcement that there was to be a grafting-on of a new and modern space, for a Center for Human Values. At the completion of the new Hall, though, there was going to be a grand ceremony for its opening. The president and a vice-president of the university, the relevant dean, and the donors. Unlike the donors’ appearance in medieval paintings, humbly marginalized in the company of saints, these donors were the saints who made it all possible. The physical entity, the annex, was to be named after its donor, Louis Marx Jr., and multiple aspects of the Center’s intellectual embodiment after its donor, Laurance S. Rockefeller. Both would be present to be honored, thanked, and feted to celebrate the opening.

At the completion of the new Hall, though, there was going to be a grand ceremony for its opening. The president and a vice-president of the university, the relevant dean, and the donors. Unlike the donors’ appearance in medieval paintings, humbly marginalized in the company of saints, these donors were the saints who made it all possible. The physical entity, the annex, was to be named after its donor, Louis Marx Jr., and multiple aspects of the Center’s intellectual embodiment after its donor, Laurance S. Rockefeller. Both would be present to be honored, thanked, and feted to celebrate the opening. When Rockefeller got up to speak, there was not much need for him to say much, for he was at once presented with a gift, in honor of the occasion, of a painting. It was, perhaps surprisingly, wrapped and taped up in packing paper, as if it had been meant to reach him through the post. After a moment’s perplexity Rockefeller forcefully attacked the wrapping. Someone was bringing up an implement, a knife or scissors, but paper was already flying everywhere, frustratingly resisting tape pulled off forcibly over the edges, and Rockefeller held up the picture in triumph. Hard to remember what it was, I trust it was something appropriate.

When Rockefeller got up to speak, there was not much need for him to say much, for he was at once presented with a gift, in honor of the occasion, of a painting. It was, perhaps surprisingly, wrapped and taped up in packing paper, as if it had been meant to reach him through the post. After a moment’s perplexity Rockefeller forcefully attacked the wrapping. Someone was bringing up an implement, a knife or scissors, but paper was already flying everywhere, frustratingly resisting tape pulled off forcibly over the edges, and Rockefeller held up the picture in triumph. Hard to remember what it was, I trust it was something appropriate. The philosophy department was large and very diverse, philosophically; it had been built up with a zoo-director’s ideal of having at least one, but not more than two, specimens of each species. So I certainly can’t talk here about all my colleagues, but some stand out. In philosophy of science we had the famous Norwood Russell Hanson (he would need a whole post of his own). On the other extreme there was a youngish man that I would often come across on the campus, walking with an umbrella, wearing a long raincoat, regardless of weather. No matter how I approached or said hello, we never reached the point of eye contact. So all I have is hearsay, in all likelihood not too trustworthy. He had come to the campus as a freshman at age 18, and never left. His undergraduate thesis was on Love in 19th century philosophy, his master’s thesis on Love in the German Romantics, his dissertation on Love in Schelling and Schleiermacher. Now he taught German philosophy and was said to have just had his first date. We must assume that he was well prepared, but nothing further was known.

The philosophy department was large and very diverse, philosophically; it had been built up with a zoo-director’s ideal of having at least one, but not more than two, specimens of each species. So I certainly can’t talk here about all my colleagues, but some stand out. In philosophy of science we had the famous Norwood Russell Hanson (he would need a whole post of his own). On the other extreme there was a youngish man that I would often come across on the campus, walking with an umbrella, wearing a long raincoat, regardless of weather. No matter how I approached or said hello, we never reached the point of eye contact. So all I have is hearsay, in all likelihood not too trustworthy. He had come to the campus as a freshman at age 18, and never left. His undergraduate thesis was on Love in 19th century philosophy, his master’s thesis on Love in the German Romantics, his dissertation on Love in Schelling and Schleiermacher. Now he taught German philosophy and was said to have just had his first date. We must assume that he was well prepared, but nothing further was known. We had a then (or perhaps a bit previously) famous metaphysician, Paul Weiss. Yale is not a simple entity, it is actually a cluster of residential colleges, each being a dormitory with a well-appointed suite for the Master as well as rooms for some favored, single, presumed to be celibate, faculty. Paul Weiss had the penthouse of one of the modern colleges, I think it was Ezra Stiles, architecturally famous, designed by Eero Saarinen (a Yale graduate, naturally).

We had a then (or perhaps a bit previously) famous metaphysician, Paul Weiss. Yale is not a simple entity, it is actually a cluster of residential colleges, each being a dormitory with a well-appointed suite for the Master as well as rooms for some favored, single, presumed to be celibate, faculty. Paul Weiss had the penthouse of one of the modern colleges, I think it was Ezra Stiles, architecturally famous, designed by Eero Saarinen (a Yale graduate, naturally).

“Some of you may have heard that we had a death here last year” the instructor said. ” I can assure you it was not an accident, there was nothing wrong with the parachute or with the jump, it was a suicide.

“Some of you may have heard that we had a death here last year” the instructor said. ” I can assure you it was not an accident, there was nothing wrong with the parachute or with the jump, it was a suicide. The jump master, with a pretty obvious knife strapped to his calf, opens the door, to the sound of air rushing by at 60 mph. He motions to you, you get into the door. There are struts under the wing that you step out on, holding on to the top. A bit like standing up on a motorcycle, except that you have all those things to hold on. Well, I shouldn’t say this too blithely. As you stand on that strut, it does feel a lot like standing on the outer parapet of a roof, it’s a feeling that is located somewhere around your stomach. You remember the cartoons, in the barn, of jumpers who refused to let go … . The jump master hits your leg, it’s your signal, you jump off backward.

The jump master, with a pretty obvious knife strapped to his calf, opens the door, to the sound of air rushing by at 60 mph. He motions to you, you get into the door. There are struts under the wing that you step out on, holding on to the top. A bit like standing up on a motorcycle, except that you have all those things to hold on. Well, I shouldn’t say this too blithely. As you stand on that strut, it does feel a lot like standing on the outer parapet of a roof, it’s a feeling that is located somewhere around your stomach. You remember the cartoons, in the barn, of jumpers who refused to let go … . The jump master hits your leg, it’s your signal, you jump off backward. In the war, an old soldier had told me, they parachuted from 800 feet, hardly high enough to slow the fall. I’m sure I wasn’t quite that low before deploying. But still the landing happened a bit too soon, I fell lengthwise, there was a wind that caught the canopy, and I got dragged through the corn stubble in this farm field. Hit quick release button! — yes, sure, but contrary to all theory, it took hitting and pulling, no instant response … Got myself together, gathered up the shrouds and canopy, carried them in my arms through the field, and through the next field, and through the next …

In the war, an old soldier had told me, they parachuted from 800 feet, hardly high enough to slow the fall. I’m sure I wasn’t quite that low before deploying. But still the landing happened a bit too soon, I fell lengthwise, there was a wind that caught the canopy, and I got dragged through the corn stubble in this farm field. Hit quick release button! — yes, sure, but contrary to all theory, it took hitting and pulling, no instant response … Got myself together, gathered up the shrouds and canopy, carried them in my arms through the field, and through the next field, and through the next …

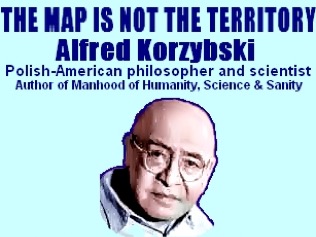

Hayakawa had studied in the Institute for General Semantics, in Chicago. This had been founded by a Polish aristocrat emigre, Alfed Korzybski, an erstwhile intelligence officer in the Russian army — one of the few, I think, who wasn’t murdered in the 1917 Russian revolution. The principles of General Semantics were both simple and profound:

Hayakawa had studied in the Institute for General Semantics, in Chicago. This had been founded by a Polish aristocrat emigre, Alfed Korzybski, an erstwhile intelligence officer in the Russian army — one of the few, I think, who wasn’t murdered in the 1917 Russian revolution. The principles of General Semantics were both simple and profound: These were the days of scholastic disputation, and the first argument was that this was not possible: there could not be offspring of two distinct kinds of being, not even of horse and ox, let alone of human and demon.

These were the days of scholastic disputation, and the first argument was that this was not possible: there could not be offspring of two distinct kinds of being, not even of horse and ox, let alone of human and demon. The Great Solar Eclipse of February 26, 1979 was going to be spectacularly visible in Bozeman, Montana, so the university there decided on a great celebratory event that would bring together scholars, artists, physicist, poets, writers, musicians … This was organized by Michael and Lynda Sexton, in English and Philosophy respectively — I was going to know them well afterward, because they involved me in their fabulous magazine Corona.

The Great Solar Eclipse of February 26, 1979 was going to be spectacularly visible in Bozeman, Montana, so the university there decided on a great celebratory event that would bring together scholars, artists, physicist, poets, writers, musicians … This was organized by Michael and Lynda Sexton, in English and Philosophy respectively — I was going to know them well afterward, because they involved me in their fabulous magazine Corona.

Michael Scriven … of course I was in awe! We all learned about him, he had singlehandedly demolished the Hempel-Oppenheim theory of explanation with his clever counter-examples. And there were rumors about him, wasn’t he rich, a man of the world?

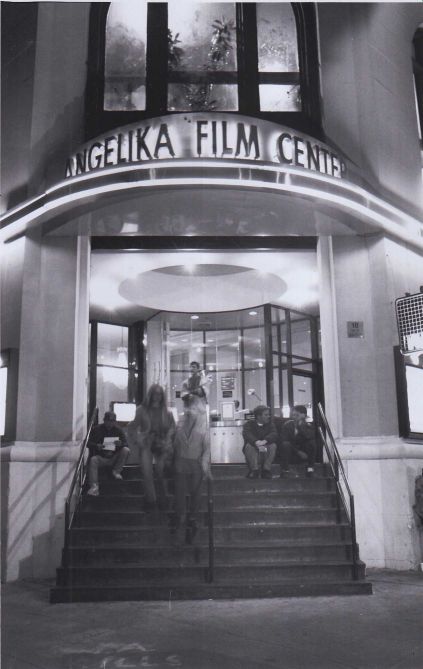

Michael Scriven … of course I was in awe! We all learned about him, he had singlehandedly demolished the Hempel-Oppenheim theory of explanation with his clever counter-examples. And there were rumors about him, wasn’t he rich, a man of the world? This was in New York, I was going with a friend to an art movie theater, the Angelika, in Greenwich Village. I wanted rather to impress her but it was not going very well. I was just speaking about how lucky we were, so healthy, in life and limb, not even having to wear glasses.

This was in New York, I was going with a friend to an art movie theater, the Angelika, in Greenwich Village. I wanted rather to impress her but it was not going very well. I was just speaking about how lucky we were, so healthy, in life and limb, not even having to wear glasses.