In the fall of 1965 I was writing my dissertation and applying for jobs. The universities were expanding and we were giving job talks all over the place. One of mine was at Indiana University.

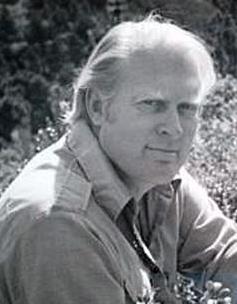

When I arrived a tall, handsome blond man took charge of me. “Hi, I’m Michael Scriven, I’m to be your host. Your talk isn’t till tomorrow, and we have nothing on till dinner. So let’s go to my house for a bit.”

Michael Scriven … of course I was in awe! We all learned about him, he had singlehandedly demolished the Hempel-Oppenheim theory of explanation with his clever counter-examples. And there were rumors about him, wasn’t he rich, a man of the world?

Michael Scriven … of course I was in awe! We all learned about him, he had singlehandedly demolished the Hempel-Oppenheim theory of explanation with his clever counter-examples. And there were rumors about him, wasn’t he rich, a man of the world?

“First of all”, he said, “we have to go pick up my car from the mechanic”. Not some serious repair, I hope? “No, not at all, he is replacing the headlights. The new halogen lights aren’t available here yet, but I had some imported from Europe, he’s putting them in”. So we went there and got into his very large Cadillac with its new lights, On the way out of town he began to tell me about the house, which he had contracted and designed himself.

“First of all a friend flew me over the area to do some aerial photography, then I went to the land office to find out who owned the hills that looked attractive in the photos. You’ll see, the house has a good view over the valley”.

Coming through the gate we wended our way through the peacocks. (“I used to have an ocelot”, he said, “but the farmers claimed he was worrying their animals, totally untrue. I had to give it to a zoo”.) Just before the door was a huge hanging mobile (Alexander Calder, he told me) and we entered the kitchen. Poor cat, must be hungry — Michael went to something like a small oven (“Got this recently, but in the end I’m only using to warm the catfood”). I had no idea what it was; later, when I became less ignorant, I realized it must have been an early microwave.

We toured the house, which was built into the hill, so we had come in on the second floor. The floor below had the master suite and his office, looking out over the valley. There were still rather a lot of leaves on the trees (“The view is magnificent in the winter!”) and the office would have been rather dark if it weren’t for lighting that seemed to come from every direction in the room. We went back upstairs, and arranged ourselves in a conversation area, with sherry and nuts (“Do you like macadamia nuts?” — only God, as far as I knew, would know what they were, but I was very appreciative.)

“But wait! Before you tell me all about your philosophy, have you ever heard a four-thousand dollar Hi-Fi turned way up high?” No, Michael, that would be amazing … I was volubly admiring it as soon as he turned it off and we could speak again … And we talked. In fact, Michael could be a good listener. I began to relax.

“Some more sherry?” As he spoke, as it was getting dark now, the lights turned on automatically. He looked up.

And I didn’t say a word.

I remember Bas’ job talk, which kept the graduate students at IU gabbing for a month. Scriven left Indiana for Berkeley, and replaced the Cadillac with a Couger, a huge Ford substitute for a sports car. Scriven hired me as a ghost writer the summer after my first year at Princeton. He had an H shaped house over Point Reyes. I had one leg of the H and Scriven and his then lady friend, Mary Ann Warren i think, had the other. I was hired to write a textbook in 6 weeks. Week after week I tried to meet with him to review my drafts. He was always too busy. Two days before the end I told him it was his last chance to review with me. He promised he would be in my room first thing in the morning,and he was, arm around Mary Ann. Two steps into the room he stopped and said “Mary Ann, there is no carpet in Clark’s room! Insufferable! Quick to the Couger.” As I was packing up, they returned the next day with an oriental carpet, probably worth a year of my salary.

LikeLike